In the southwest of the Pacific Ocean lies the unique Tasman Sea, which hosts a spectacular volcanic world on its seabed. We invite you to learn about this enigmatic sea, its location, history, formation, climate, flora, fauna and impressive volcanoes.

Indice De Contenido

Location of the Tasman Sea

The Tasman Sea is a marginal sea located in the south-western part of the Pacific Ocean, between the south-east coast of Australia and Tasmania to the west and New Zealand to the east. It is considered marginal in oceanographic terms because it is a sea on the edge of two large territories, partially enclosed by large peninsulas or island chains.

It is considered a marginal sea in terms of oceanography because it is located on the edge of two large territories and is partially enclosed by large peninsulas or chains of islands. You may be interested to know that the Macquarie Islands Marine Reserve is also in the Pacific.

The Tasman Sea is colloquially known in Australian and New Zealand English as the Ditch. For example, it is very common in the region to hear the expression “crossing the Ditch”, which can mean travelling from New Zealand to Australia or vice versa.

This diminutive term, the Ditch, is similar to the Pond used to refer to the North Atlantic Ocean.

The sea was named after the Dutch navigator Abel Janszoon Tasman, who sailed it in 1642 and was the first recorded European to reach New Zealand and Tasmania. We recommend you read about the Coral Sea Natural Park, close to the Tasman Sea.

Later, in the 1770s, Lieutenant James Cook sailed extensively in the Tasman Sea as part of his first voyage of exploration.

With a maximum depth of over 5,200 metres, the seabed is characterised by the Tasman Basin.

The South Equatorial Current and trade wind drift feed the southward-moving East Australian Current, which is the dominant influence along the Australian coast.

From July to December its influence is minimal and colder waters from the south can penetrate as far south as 32°S.

In the eastern Tasman Sea, the surface circulation is controlled by a current from the western Pacific from January to June, and by colder sub-Antarctic waters moving northwards through Cook Strait from July to December.

These different currents result in a generally temperate climate in the southern Tasman Sea and a subtropical climate in the northern Tasman Sea.

Located in the westerly wind belt known as the “Roaring Forties”, the sea is known for its stormy character.

The sea is crisscrossed by shipping lanes between New Zealand and south-eastern Australia and Tasmania, and its economic resources include fisheries and oil fields in the Gippsland Basin at the eastern end of Bass Strait.

The Southern Ocean is crisscrossed by depressions running from west to east. The northern limit of these westerly winds is near 40°S.

During the austral winter, from April to October, the northern branch of these westerly winds turns north and faces the trade winds.

As a result, the sea often receives southwesterly winds during this period. During the Australian summer (November to March), the southern branch of the trade winds rises against the westerly winds and creates more wind activity in the area.

Boundary

The International Hydrographic Organisation defines the boundaries of the Tasman Sea as follows

- On line A west from Gabo Island, near Cape Howe, 37°30’S, to the north-east point of East Sister Island (148°E). From there follow the 148th meridian to Flinders Island.

- From this island a line runs east from Vansittart Shoals to Cape Barren Island. From this point, which is the easternmost point of the island, you reach Eddystone Point, which is 41°S in Tasmania.

- From there it continues along the entire east coast to South East Cape, the southernmost point of Tasmania.

- To the north, the 30°S parallel is marked from the Australian coast eastwards to a line joining the eastern ends of Elizabeth Reef and South East Rock.

- It then follows this line south to Southeast Rock, which is an outcrop of Lord Howe Island.

- To the north-east it leaves South East Rock and reaches the northern tip of the Three Kings Islands, from where it continues to the North Cape in New Zealand.

- Then to the east, in Cook Strait, you start a line that connects to the southern end of the Dirty Land in front of

- Cape Palliser (Ngawi) and the lighthouse at Cape Campbell (Te Karaka).

- Then, in Foveaux Strait, a line is drawn between the Waipapa Point light and the East Head of Stewart Island, Rakiura.

- To the south-east, a line is drawn from Southwest Cape, Stewart Island, following the Snares, to Northwest Cape, Auckland Island, across the island to its southern tip.

- Finally, the South A line runs to the southern point of Auckland Island and connects with the Southeast Cape, the southern point of Tasmania.

History of the Tasman Sea

Historical records indicate that this sea takes its name from the island of Tasmania, which was discovered in the 17th century by the Dutch explorer and trader Abel Janszoon Tasman.

Later, in the 1770s, the British explorer James Cook explored this sea extensively as part of his first voyage of discovery.

Over time, interest in its islands, resources and seabed grew.

In 1793, an Italian captain in the service of Spain, Alejandro Malaspina, famous for leading one of the great scientific voyages of the Enlightenment, the Malaspina Expedition, sailed through its waters.

During his voyage, he anchored in Doubtful Sound on the South Island of New Zealand and in Sydney, Australia.

New Zealanders Lieutenant John Moncrieff and Captain George Hood were also the first to attempt a transatlantic flight from Australia to New Zealand on 10 January 1928, but they disappeared shortly after taking off.

Radio signals from their plane were received for 12 hours after they left Sydney, but despite a number of alleged sightings in New Zealand and many ground searches in the following years, no trace of the aviators or their plane has ever been found.

Formation

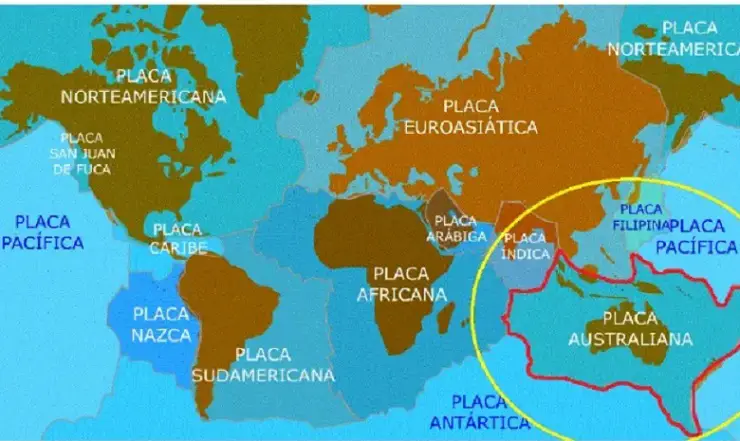

The Tasman Sea was formed during the separation of eastern Australia from the continental margin of the Lord Howe Rise, now a largely submerged plateau, during the Late Cretaceous and Early Paleogene, some 85 Ma or millions of years ago.

Based on estimates of the age of the crust of the Lord Howe Ridge and geosynclinal theory, these studies suggested the presence of an extinct ridge or uplift between Australia and the Lord Howe Ridge, which formed after the Palaeozoic.

However, these studies erroneously suggested that the Dampier Ridge, a marine formation in Papua New Guinea waters, was probably the extinct axis of this extensional system.

Research continued for a long time, and years later an updated interpretation of the southern magnetic anomalies was presented as the exact location of the extinct spreading centre in the Tasman Sea, and it was proposed that spreading ceased at about 60 Ma.

The age of the oldest crust formed in the basin has been controversial and more recent studies have proposed a later cessation date, following more detailed studies of the extensional axis.

Regional reorganisation of the ridge may have occurred prior to the opening of the Tasman Sea, and several authors argue that the Middleton and Lord Howe basins preceded the formation of the Tasman Sea.

They also note that there was a westward jump in the ridge that shifted active spreading west of the Lord Howe uplift, possibly at ca. 75 Ma.

These studies included a complex model of the opening of the Tasman Sea in which they proposed that several episodes of rotation of the adjacent continental blocks occurred during the opening of the basin.

It has also been suggested that the conjugate boundaries of the ocean basin were formed by a series of discrete continental blocks, rather than as a two-plate system.

Carmen Gaina, a dedicated Norwegian researcher in the Tasman region, and her team of collaborators have carried out a study of plate tectonics in the region and have suggested that there was some asymmetry in the centre of spreading between chron 33y and 27o, with higher rates of crustal accretion on the eastern flank.

It is proposed that extension developed first in the south due to movement of the Challenger Plateau relative to the Lord Howe uplift, and that an earlier faulted rift formed in the Bellona Trench.

Other scientists such as Lanyon et al. in 1993 suggested that the Balleny plume may have been a major influence on the development of the southern Tasman Sea, and then in 1994 Weaver et al. also suggested an earlier influence of a plume with the New Zealand Rift or tectonic rifting of Marie Byrd Land in the eastern Tasman Sea.

There is some doubt as to whether the spreading centre was a mid-ocean ridge spreading centre or whether it was a back-arc basin, which is a geological basin, submarine feature associated with island arcs and subduction zones, as noted by Schellart et al. in 2006, since westward subduction east of the Lord Howe uplift is suggested by several models.

Weissel and Hayes in 1977 had suggested that a subduction zone was not present in this region during basin formation.

The width of the Lord Howe Rise continental belt is greater than that of many global backarc basins, suggesting that the distance from the rift to the spreading centre is too great for a backarc basin to have formed.

Features of the Tasman Sea

The Tasman Sea is unique in that it has several climatic zones.

It is also interesting in terms of its boundaries, as it bathes several different regions.

In the north it runs along the coasts of the Australian state of New South Wales. In the south, it runs along the Macquarie Ridge and the west coast of New Zealand.

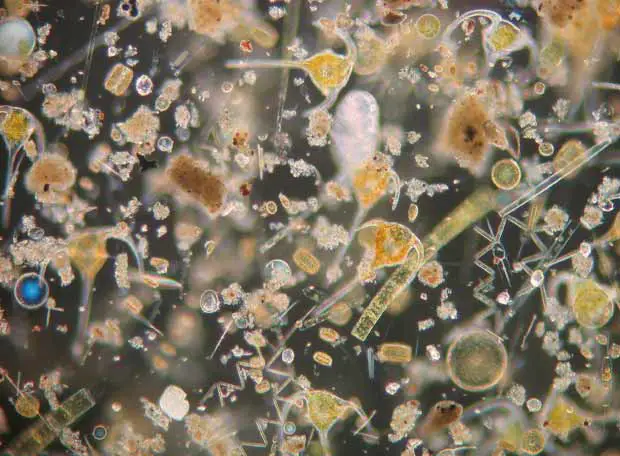

This sea has a depth of 5,493 metres and its base is formed by the globigerine lag. South of New Caledonia there is a small area of pteropod lag and south of 30°S there is siliceous lag.

To the north, it merges with the Coral Sea and encloses a body of water approximately 2,250 km wide and 2,800 km from north to south, with a surface area of 2,300,000 km2.

The Climate

The sea is located in a variety of climates: tropical, subtropical and temperate, which produce a wide range of flora and fauna, creating a unique habitat.

This climatic diversity affects the ocean currents in the area. Hot air masses are generated throughout the area, causing water temperatures to rise up to 26 degrees Celsius.

The southern part of the sea is crossed by depressions running from west to east, and the northern limit of these westerly winds is around 40°S. Further south, the waters are even colder due to the proximity of Antarctica.

During the austral winter, from April to October, the northern branch of these westerly winds turns north and faces the trade winds.

As a result, the sea often receives south-westerly winds during this period. During the Australian summer (November to March), the southern branch of the trade winds rises against the westerly winds, creating more wind activity in the area.

Flora and Fauna

The seabed flora of the Tasman Sea includes a large number of macroalgae.

The diversity and endemism of the marine macroflora of these temperate regions is among the highest in the world, with approximately 125 species of green algae, 225 species of brown algae and 800 species of red algae.

Although Tasmania’s flora remains poorly known due to a lack of seaweed specialists, south-eastern Tasmania has probably the highest proportion of localised endemic species in Australia.

Tasmania’s cool-climate species include the largest Australian seaweeds, notably giant kelp, bull kelp, strap kelp, common kelp and other large brown algae such as crayfish.

Tasmanian waters are also characterised by the presence of several species of sub-Antarctic macroalgae not recorded elsewhere in Australia.

Bull kelp, undaria and fused algae are currently exploited commercially.

Six marine seagrass species are also recorded, with two additional species occurring in estuaries.

Seagrass habitats in Tasmania, as in other parts of the world, have been lost, fragmented and damaged by development and poor catchment management through practices such as sewage and stormwater discharges, urban runoff, dredging, shipping and land reclamation.

In terms of wildlife, a deep-sea research vessel, the RV Tangaroa, explored the sea and found 500 species of fish and 1,300 species of invertebrates. Researchers also found the tooth of a megalodon, an extinct shark.

There are a large number of marine invertebrate species, probably more than 100,000. However, our knowledge of species in different habitats is very patchy: in particular, the number of deep-sea benthic fauna is enormous but almost unknown.

In contrast, large crustaceans (lobsters, prawns and crabs), which are an important commercial resource in southern Australia, are relatively well described.

Of particular note are the southern rock lobster and the giant deep-sea crab Pseudocarcinus gigas, the largest crab in the world by weight.

Molluscan species such as abalone, oysters and scallops are also of direct economic importance in Tasmania and their status and biology are also relatively well understood.

In particular, important commercial fisheries have developed for black abalone and, to a lesser extent, green abalone and scallops.

In the cooler waters of Tasmania and Victoria, the Maori octopus is commercially important and is one of the largest octopuses in Australia (arms over 3 m long and weighing over 10 kg have been recorded).

Other molluscs are also well represented in South Australia and Tasmania, including sea slugs, of which over 500 species have been recorded. Frills and cowries are a relict fauna in Tasmania and South Australia, with some very rare species. In Tasmania, some species are highly sought after by shell collectors.

Echinoderms (sea stars, sea urchins, feather stars, sea cucumbers, etc.) are also an important part of the fauna of Tasmanian and South Australian waters. Several species are threatened.

Tasmania’s fish fauna is very diverse and includes more than 600 species. More than 50 species are commercially exploited, with 15-20 species contributing most to the annual commercial catch.

Tasmania has some fish that are only found at the southern end of the region, particularly in the south-eastern bays and around Port Davey in the south-west.

In the shallow waters of Port Davey, sharks, rays and skates, which are common at 50m depth on the continental shelf, replace the usual mix of parrotfish, stingrays and other common inshore reef fish.

Prominent among the fishes of south-eastern Tasmania are several species of hand fish. These fish have no pelagic larval stage and are very localised in distribution. All species of handfish are protected in Tasmanian waters.

Other rare and endemic species of importance in Tasmania and South Australia include pipefish, seahorses and sea dragons.

Volcanoes under the Tasman Sea

The volcanoes on the Tasmanian seafloor have always been of interest to scientists because of their unique characteristics.

Recently, some very interesting discoveries have been made under the Tasman Sea, thanks to a group of Australian scientists who have been exploring the sea.

They found an ancient underwater world with underwater mountains and volcanoes and new life forms.

Many of these underwater mountains were found to be ancient extinct volcanoes rising from the seafloor, some three thousand metres high and about five thousand metres below the surface.

However, despite their great height, such a series of volcanoes had not been detected before, because even the highest peaks of these mountains were still two thousand metres from the sea surface, which is why they had not been discovered until now.

The studies carried out have provided new scientific evidence that the geological processes taking place there have created a transtromanic volcanic field.

The discovery was made by scientists from the Australian National University on board a CSIRO research vessel.

These researchers suggest that these underwater mountains and volcanoes are linked to a cataclysmic event millions of years ago that is thought to have caused the break-up of Australia and Antarctica, which began about 60 Ma ago and ended about 30 Ma ago.

In this rift, Antarctica gradually separated from Australia from about 66 Ma to the present day.

In the area where Tasmania is located, these volcanoes were formed about 35 Ma ago.

In this underwater world, it has been found that some of these volcanoes have formed a kind of “highway” of ocean currents that the fauna of the area use to move around, especially the whales that move quickly through these valleys and seamounts.

The discovery was made by a team of scientists who spent 25 days in the Tasman Sea analysing what is produced there.

This is the process by which microscopic phytoplankton convert sunlight into the carbon that sustains entire marine ecosystems.

What happened was that while other crew members were observing the local marine life, they were also looking for signs of phytoplankton activity and mapping sections of the unexplored seabed using special sonar.

When they were about 400 km from the island of Tasmania, they found this huge chain of submerged volcanic mountains thousands of metres below the sea surface.

The scientists now want to carry out further studies to see what is there – a whole volcanic world full of life and to observe the animal and plant species, many of which may be unknown to man.

So far, researchers have been able to establish that the volcanoes in this region do not belong to any of the three main groups of volcanoes already established:

- The large oceanic islands such as Samoa.

- The explosive Ring of Fire volcanoes.

- The oceanic volcanoes of the offshore mountain chain.

In their work, the scientists used computer reconstruction methods to simulate past tectonic plate movements, as well as the chemical fingerprint of volcanic roots, to determine the origin of hundreds of eruptions along Australia’s east coast and Tasman Sea.

As a result of their studies, the scientists believe that the eruptions are caused by the seafloor of the Pacific plate being pushed underneath the Australian plate.

This is known in scientific jargon as subduction, the process by which one plate sinks beneath the other on its way into the Earth’s interior, and the oceanic crust breaks apart and deforms under extreme pressure and temperature.

The remnants of the crust, according to scientists, accumulate in a zone called the Mantle Transition Zone, located 400-600 km below the surface.

When these remnants return to the surface, they are likely to melt and create new volcanoes and eruptions.

Tasman Sea Islands

The Tasman Sea has several groups of islands in the middle of the sea with unique indigenous populations.

Apart from the offshore islands close to the mainland of Australia and New Zealand, perhaps the most famous of these is Tasmania, located 240 km south of Australia.

Its capital, Hobart, is in the south of the island, as are the city’s local government areas.

Separated from Australia by the Bass Strait, Tasmania is located on a geologically active site, so scientists believe that Tasmania was once part of the Australian mainland, but was separated by certain processes.

It is now the largest of Australia’s protected areas because of the unique animals that live there. The most famous is the Tasmanian Devil.

Other important islands are

Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island is the southernmost island development of a modern coral reef.

It is an irregular crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea, 600 km east of Port Macquarie, 780 km northeast of Sydney and about 900 km southwest of Norfolk Island.

It is about 10 km long and between 0.3 and 2.0 km wide, with an area of 14.55 km2, of which only 3.98 km2 is the lower, developed part of the island.

Along the west coast is a semi-enclosed sandy lagoon protected by coral reefs.

Most of the population lives in the north, while the south is dominated by wooded hills rising to the island’s highest point, Mount Gower, at about 875m (2,990ft).

The Lord Howe archipelago comprises 28 islands, islets and rocks. To the north is a group of seven small uninhabited islands called the Admiralty Group.

Lord Howe Island was first sighted on 17 February 1788 by Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball, commander of HMS Supply, en route from Botany Bay to establish a penal settlement on Norfolk Island.

It later became a supply port for the whaling industry and was permanently settled in June 1834.

As whaling declined, the 1880s saw the start of the global export of the endemic kentia palm, which remains an important part of the island’s economy.

The other continuing industry, tourism, began after the end of the Second World War in 1945.

The Lord Howe Island group is part of the state of New South Wales in Australia and is legally an unincorporated area administered by the Lord Howe Island Council, which reports to the New South Wales Minister for Environment and Heritage.

The currency is the Australian dollar. Commuter airlines offer flights to Sydney, Brisbane and Port Macquarie.

UNESCO considers the Lord Howe Island Group to be a World Heritage Site of World Natural Importance.

Most of the island is virtually untouched forest, with many plants and animals found nowhere else in the world.

Other natural attractions include the diversity of landscapes, the variety of upper mantle and oceanic basalts, the world’s southernmost barrier reef, nesting seabirds and a rich historical and cultural heritage.

The Lord Howe Island Act 1981 established a ‘Permanent Park Reserve’ (covering approximately 70% of the island).

The island was added to the Australian National Heritage List on 21 May 2007 and to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.

The surrounding waters are a protected area called Lord Howe Island Marine Park.

Ball Pyramid

It is an erosional remnant of a shield volcano and caldera, located 20km south-east of Lord Howe Island.

It is a huge rock, 562m high, but only 1,100m long and 300m wide, making it the tallest volcanic pile in the world.

The Ball Pyramid is part of the Lord Howe Island Marine Park and is located more than 643 kilometres north-east of Sydney, New South Wales.

Steep, eroded and formed 6.4 million years ago, the Ball Pyramid sits at the centre of an underwater shelf and is surrounded by rough seas that make any approach difficult.

Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island is Australia’s main overseas territory, located between New Zealand and New Caledonia, 1,412 km directly east of Evans Head in Australia and about 900 km from Lord Howe Island.

Together with neighbouring Phillip Island and Nepean Island, they form the Norfolk Island Territory.

At the 2016 census, it had a population of 1,748 and a total area of about 35 km2. The capital is Kingston.

The earliest known settlers of Norfolk Island were East Polynesians, but they had left by the time Britain colonised the island as part of its settlement of Australia in 1788.

The island served as a penal settlement for convicts from 6 March 1788 to 5 May 1855, except for an 11-year hiatus between 15 February 1814 and 6 June 1825, when it was abandoned.

Permanent civilian settlement on the island began on 8 June 1856, when the descendants of the Bounty mutineers were resettled from Pitcairn Island.

In 1914, the United Kingdom ceded the island to Australia to be administered as an Overseas Territory, but as a separate and distinct settlement.

The native Norfolk Pine is a symbol of the island and appears on its flag.

Pine is a major export for the island as it is a popular ornamental tree in Australia, where two related species grow, and indeed around the world.

Harbours

Among the various ports that bathe the Tasman Sea are the following

- Hobart: Located south of Tasmania Island on the Derwent River, it is one of 12 ports managed by the Tasmanian Ports Corporation, also known as Tasports.

- Devonport: Situated north-west of Tasmania on the Mersey River. It is the main sea gateway to Tasmania and is home to the two luxury passenger ferries that link this port to Melbourne.

- Huon Marina: Situated south of Huonville and north of Dover, Port Huon Marina is ideally located for yachting enthusiasts to take advantage of this special cruising area.