A galleon was a type of sailing ship used in the 16th century for both warfare and trade with other ports. In today’s article, we will learn all about this ship, its history, characteristics and more.

Indice De Contenido

What is a galleon?

The galleon was a type of sailing ship that consisted of at least three or four masts, the sails of which were generally set in cross sails. The use of this vessel dates back to the middle of the 16th century. It consisted of a large, high-boat that was moved by the action of the wind.

In the same sense, it could be said to be a derivative of the carrack, but with the speed of the caravel. During wars, galleons were ships of great power, but they were also versatile, being used for trade and exploration.

By the middle of the 16th century, the galleon was chosen as the main warship of the European nations, and its design was used in later years to create new models for their warships.

The history

If the calavera is considered a Portuguese design, the galleon is a Spanish invention, created to provide the Crown with a ship that could compete with the cargo capacity of the nao and the speed and manoeuvrability of the caravel. The purpose was to explore and trade with the newly discovered Indies.

The first mention of the term is uncertain, as at that time there was no precise nomenclature to define the different types of ship. For this reason, the galleon was used for both fishing and military purposes. In 1567, the galleon was distinguished from the naos as a military term, called “Galeones del Rey” (King’s Galleons), and years later this term was applied to warships.

In the same sense, the term galleon appears in documents before his time. Like the frigate and the brigantine, the galleon appears as a smaller variant of the galley, as can be seen from the Annali Genovesi, which mention galleons with 80, 64 and 60 oars, used for their speed and manoeuvrability in the 12th and 13th centuries. It is possible that during the Crusades the galleon and the galleot were the same type of ship.

In later years, the term was used only to describe sailing ships. There is evidence, however, that the Venetians used warships without oars as early as the Battle of Durazzo in 1081. The European war fleets were always rowing ships until the discovery of new routes in the 15th century made it clear that new ships had to be designed.

As the chronicles of the Battle of Preveza in 1538 show, a ship called a galleon took part in the battle with several Turkish galleys, suggesting that heavily armed ships were already in existence.

Although the galleon is known to have been a Spanish invention, Francis I of France had ordered the construction of ships called nefs-galères or galions as early as the 16th century. Similarly, the armed ships of the Order of Malta included a galleon that took part in the battle of La Rochelle in 1628 under the name of Galleon de la Religion during the reign of Louis XIII.

In his Testament Politique, Cardinal Richelieu, the father of the French navy, wrote that if France could build strong galleys and galleons, the Spanish would not be able to sail their seas. In 1671, however, there were no more galleons on the French naval lists, as these ships were simply called “vaisseaux”.

First designs

In the early days of galleon design, Spanish construction was concentrated on the Atlantic coast, mainly in Cantabria, Vizcaya and Cadiz, and later in Lisbon. The Mediterranean coast, although the main source of ships at the time, was gradually losing its importance and the emphasis was placed on the construction of smaller vessels.

On occasion, the Spanish Crown bought ships in other European possessions, such as Sicily or Flanders. In 1610, construction began in the Caribbean, particularly in Havana, whose shipyards were notable for their early access to tropical woods such as mahogany.

In the beginning, galleons were built from native European woods, as tropical woods of superior quality had not yet been tested for shipbuilding in Europe. Oak was usually used for the keel, frames and other structural elements, pine for the masts and spars, and a variety of woods for the planking.

The planking was usually made of continuous planks, although in some northern European countries a clinker system was used, with overlapping planks. The whole process of building a galleon took about two years.

What was it used for?

The galleon was a multi-purpose ship, designed to meet the needs of a fleet that could not meet them at the time. There was a need for special ships that could carry a cargo and fight on long voyages. Over the years, the functions of the galleon were taken over by other types of ships.

On the other hand, the war galleon is defined as a specific 17th century type with greater strength and armament, which led to the development of new designs for the following century. Its function as a cargo ship was replaced by the Dutch filibote or flute, which was lightly armed but more economical and efficient. Similarly, smaller ships such as brigs replaced the smaller galleons.

The superstructures were reduced in size and height, the rigging was rationalised, the sails were fragmented and the structure lightened. From the middle of the 18th century, lateen sails were replaced by aurora sails. The storm jib and later the bait boat were also replaced.

Both the galleon and other smaller vessels continued to be used in Spain and other European nations. Later, new designs were created, but the stagnation of the Spanish administration and measures such as the Inquisition’s prohibition of books from Protestant nations, including shipbuilding manuals, had a negative effect, resulting in the advantage of the English and French navies.

Improvements and modifications

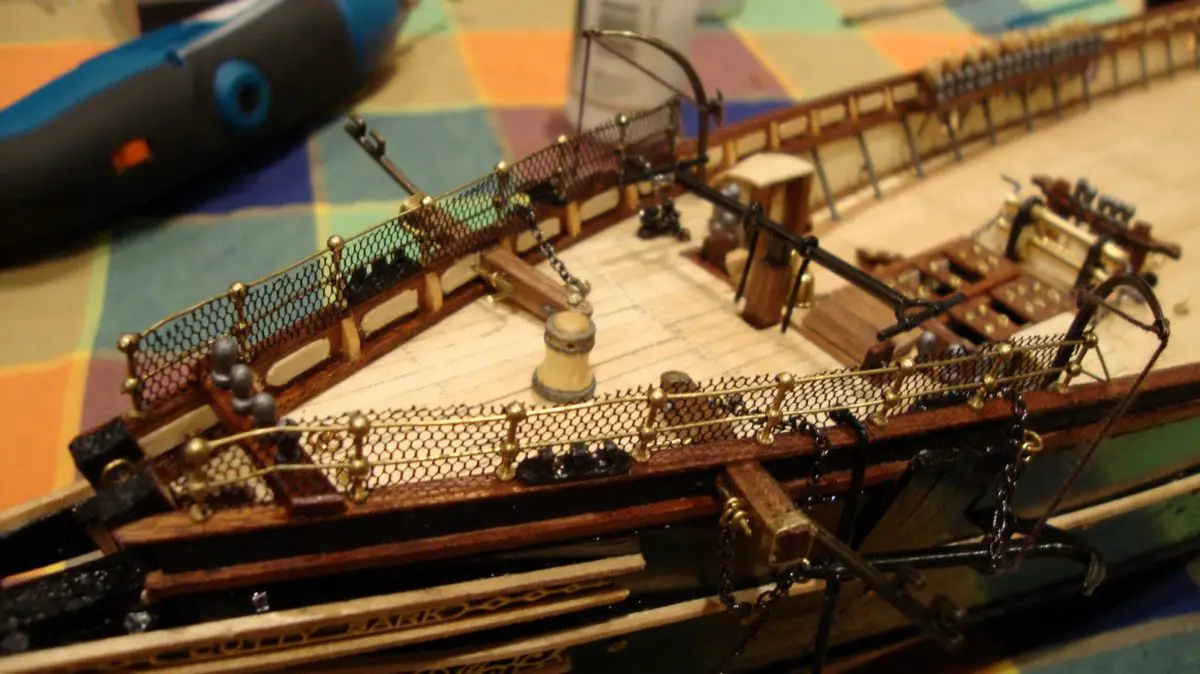

There is only one surviving galleon today, known as the hull of the Vasa, which was salvaged in 1961. All that is known about this class of ships is derived from historical documents, artistic depictions, models preserved as votive offerings and archaeological evidence. Throughout the 20th century, several reliable representations of this type of ship were made.

In 1973, a replica of Francis Drake’s Golden Hind was built in Appledore, England, using the original techniques. This replica circumnavigated the globe and is now on display in London. A second but less accurate replica was built in Brixham in 1963.

In Spain, the Galeón Andalucía was built in Punta Umbría in 2010, a replica of a generic 17th-century Spanish galleon that sailed to Shanghai for the 2010 World Expo. The reproduction of the Japanese San Juan Bautista was completed in 1993 and is on display at the Ishinomaki theme park in the north of the country.

Characteristics of the galleon

The proportions of 14th- and 15th-century ships were determined by the Murcian formula of three, two and an ace, meaning that the length had to be three times the breadth and the breadth twice the depth. In the case of the galleon, the formula was 4:2:1, slightly shorter and wider than the galley, but longer and less high than a ship.

However, this height was significantly increased by the presence of a considerable amount of acastillaje (decks and raised structures used as a drafting platform) at the bow and stern, a feature they inherited from the galleys.

However, the element that they retained from these two ships was the spur that ran along the bowsprit, but without any offensive function and without iron reinforcements, it became an inherited platform: a platform on which the bow rigging was manoeuvred and where the crew’s gardens or latrines were located.

A 16th century manuscript gives the dimensions of the galleon: length between perpendiculars 41.3 m, length at the keel 30.5 m, breadth 10 m. Thus the galleon is consolidated as a ship longer and narrower than a ship of the line, but shorter and wider than a galley, generally weighing less than 500 tons, although some could reach 2000 tons.

Over the years the displacement varied until it reached an average of 334 tons for galleons in the royal inventory of 1556. After that, the records show an increase in size, with larger and larger ships being mentioned.

The hull

In the case of the galleon, similar changes were made to the ratchet, reducing the bulwark and replacing the round stern with a flat transom. The beam was wide at the waterline and tended to narrow, and the bulwarks were inclined inwards, providing a stability that allowed the artillery to be positioned.

In order to lower the centre of gravity, the rear part of the lower deck was sometimes reduced to compensate for the blast which caused the guns mounted there to rise. The use of portholes was also formalised by placing the guns lower and closer to the centre of gravity. In addition, the bow forecastle was moved to the stem to reduce the risk of capsizing due to air pressure and to make it easier to keep the wind to windward.

A major improvement on the galleons was the integration of the pintle, a vertical extension of the tiller. Previously, the helmsman had to manoeuvre the tiller from inside the topsides, unable to see the sails, guided by a needle or instructions from the officer on deck. However, this new integration made it possible to see the sails, which was important for navigation. The wheel rudder did not appear on galleons until years later.

Another important feature of this ship was the gallery, a gangway that extended aft and housed the officers’ latrines. This was derived from a long Mediterranean tradition, dating back to Ancient Rome, of having a platform on the outside of the hull to allow people to move around the ship without having to cross the hold.

Rigging

Although some galleons bore similarities to ships, the former had four masts, foremast, mainmast, mizzen and counter-mizzen, with square sails on the foremast and mainmast and lateen sails on the other two, this number was later changed to three. The mizzen masts leaned aft until the 17th century.

Crab and knife sails were not used. This was usually accompanied by a bowsprit sail under the bowsprit and, on larger ships, a storm pole at the end of the bowsprit. By 1620, a topsail was incorporated into the mizzen lateen sail, and this type of ship was called a frigate in various countries.

The foremast was moved aft during the 17th century. Earlier, the foremast had been moved from the forecastle and, at the beginning of the new century, from the stokehold on the forecastle deck to the stern.

The sails were divided in relation to previous ships of the same size, with more sails and less uneven size, and the rigging of the running rigging was improved. The masts were also separated by the addition of masts and mastheads, a novelty introduced by the Flemish in 1570.

The armament

With the advent of the galleon, warfare entered a new phase in which this ship was fundamental to the power of the European states, not only as a means of transport and attack for land infantry. The creation of the galleon marked the beginning of the first battles on the high seas, since at that time coastal confrontations were almost always settled without a fight.

Initially, the assault tactics developed by the Spanish followed the model used in the Mediterranean: short, long-distance battles in which large numbers of infantry attempted to board enemy ships. These assault manoeuvres were intensified when artillery was added. Artillery pieces were divided into numerous categories and calibres, but fall into three classes:

- Small, repeating guns: These were usually breech-loading guns, which made them easy and quick to use, as they were loaded through a rear chamber. These weapons were aimed at enemy troops and were mounted on swivel forks on the gunwales or other structures, but always on deck to prevent the smoke they fired from flooding the ship’s interior.

- Thick, tight-firing guns: These were ancient guns, characterised by the use of bombards or lombards, made of wrought iron and reloaded. By the time of the galleons, this artillery, along with other pieces such as the bombardeta and the pasavolante, had become obsolete, although they still appeared in the royal inventories until the 1570s. The most common type at that time was the culebrinas, some of whose smaller variants fall into the above category.

- Large curved shotguns: This last category included large-calibre, short-barrelled guns that fired large pieces from the deck in a parabolic, almost vertical trajectory. The most common types of weapon were the stone and mortar guns, which fired large projectiles of specially carved stone (bolaños), and in the mid-16th century bombs were added. However, this type of weapon was gradually abandoned until it disappeared completely around 1620.

The oldest pieces of weaponry were made of wrought iron reinforced with iron bands, also made in a similar way to wooden barrels. Over the years these weapons were made of cast iron and later of bronze. The use of bronze was more expensive, but bronze guns lasted longer and were lighter.

Before the 16th century, artillery was mounted on fixed shafts without wheels, but with the arrival of the galleons, larger pieces began to be mounted on carriage shafts with two wheels, similar to those used on land pieces. Towards the end of the century, four-wheeled shafts became widespread, as they were more suitable for use at sea. Towards the end of the 15th century, trunnions were introduced, which made it easier to adjust the inclination.

The great variety of pieces and calibres was a serious problem, so Charles V tried to reduce the number to seven pieces of between 3 and 40 pounds, six of taut shot and one mortar. The artillery was so valuable that it was not part of the ship, but was kept in the royal arsenals and equipped according to its function. Although this process was complicated, it allowed the use of all available armaments.

Decoration and ornamentation

In Spain, when a galleon was completed, the shipyard handed it over to the Crown empty and without rigging. The state was responsible for outfitting the ship, a long and costly process that could take many months. The final step before the ship could be put to sea was its decoration and christening. Decoration varied according to the importance of the ship and the resources available.

In general, it was common at the time for ships to be named after saints, virgins or other religious figures. The transom of the stern was usually painted with the image of the saint or some allusive scene in Spain. The most decorative part of the ship was the sterncastle, which usually consisted of scrolls or garlands and small carved figures, repeated according to the shape of the ship.

The topsides were protected by a dark ochre paint, but sometimes bright stripes were painted along the sides of the gunwales and castles. The carved parts were often gilded. In general, the decoration of Spanish ships was simpler than that of other European nations.

A flag was flown on each mast, as well as on other banners and pennants in other parts of the ship. These flags varied according to nation, fleet and mission, following a complex system of heraldry that included the royal arms and the ensign of the fleet commander on the captain’s ship.

The crew

At the time of the galleons, the navy was governed by the rule of one crewman per ton of cargo, although this number could vary greatly according to need and financial circumstances. For example, in 1550 it was usually one seaman for every five and a half tonnes, and in 1629 it was one seaman for every six and a quarter tonnes.

Thus, a typical 17th century galleon of about 500 tons would have 90 seamen, including at least 15 officers, 25 sailors, 20 cabin boys or aspiring sailors, 10 pages or apprentice boys, and 20 gunners.

Then there were the embarked soldiers, who would make up a company of around 125 men, a larger number than any other European nation and one that could be increased in times of war or on risky missions.

The galleons of the Indies Race were commanded by a captain-general, usually a man of noble birth and seafaring experience, who boarded the captain’s ship with a retinue of royal officers.

Similarly, the captain-general was obliged to appoint an admiral, the second man in command, who was also responsible for commanding his own ship, the almiranta, whose position was to be at the rear of the formation or at the opposite end to the capitana.

On the other hand, the captain of a ship was called the governor, the highest ranking military officer after the captain general. Each of the ships had a senior pilot, who was responsible for the course of the fleet and was on board with the captain.

On the other hand, the silver galleons that transported the silver from Peru to the Casa de Contratación in Seville had a silver master on board the capitana, who was responsible for protecting the king’s cargo and was assisted by bondsmen in the rest of the fleet. Each ship also had a veedor, who represented the king’s interests, and a scribe, who kept a record of all cargo movements on board.

Unlike other European nations in the 16th and 17th centuries, Spanish galleons had a dual command: the sea captain, the highest rank, and the war captain, usually a soldier, who commanded the troops. These positions were merged into the captain of sea and war in the decree of 1633.

The master was in charge of the ship’s government, provisioning and maintenance, while the captain was involved in administrative tasks. Unlike other ship’s offices, the master usually served on the same ship throughout his career.

That’s all for today, we hope you found the information useful. We invite you to read on: Abyss Challenger and Bigger Ships