Last Updated on May 27, 2020 by Hernan Gimenez

Indice De Contenido

- 1 La Plata River: History, Characteristics, and Much More

- 2 History of the La Plata River

- 3 La Plata River: Characteristics

- 4 Tides of the La Plata River

- 5 Location and map of the La Plata River

- 6 Soils

- 7 Contamination of the La Plata River

- 8 Plant life

- 9 La Plata River fauna

- 10 Weather

- 11 People

- 12 Current economy

La Plata River: History, Characteristics, and Much More

Updated On January 16, 2020

The La Plata River, is a decreasing intrusion of the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast of South America between Uruguay to the north and Argentina to the south.

While some geographers consider it as a gulf or as a marginal Atlantic sea, and others consider it as a river, it is generally considered to be the estuary of the Paraná and Uruguay rivers (as well as the Paraguay River, which drains into the Paraná).

History of the La Plata River

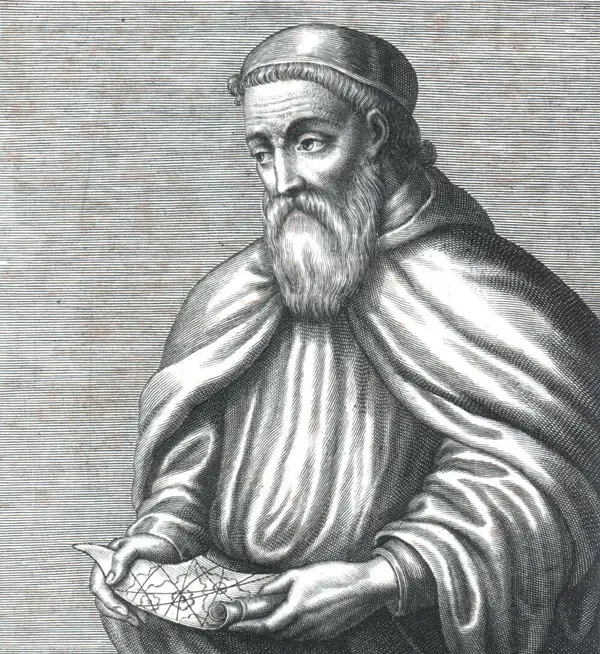

The first sighting of the river was in 1516 by Juan Díaz de Solís, a Spanish sailor born in Lebrija, Spain, who discovered the river during his search for a passage between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean.

He served as a navigator in expeditions to Yucatan in 1506 and in Brazil in 1508 with Vicente Yáñez Pinzón. He became a captain in 1512 after the death of Americo Vespucio. Two years after his appointment at this position, Díaz de Solís prepared an expedition to explore the southern part of the new continent.

His three ships with a crew of 70 men sailed from Sanlucar de Barrameda on October 8, 1515. With two officers and seven men, he followed the east coast to the mouth of the La Plata River, arriving in 1516, sailing upriver to the confluence of the Uruguay and Paraná rivers.

The small group landed in what is now the Uruguayan department of Colonia and was attacked by the natives (probably Guarani, although for a long time the deed was awarded to the Charrúas).

Only one of his men survived, a 14-year-old boy named Francisco del Puerto, supposedly because the native culture prevented them from killing the elderly, women and children. De Solís’ brother-in-law, Francisco de Torres, took over the remaining ships and crew to return to Spain.

The estuary was temporarily named in memory of Díaz de Solís after his death on its shores at the hands of unfriendly Charrua Indians. The Portuguese navigator Fernando de Magallanes arrived at the estuary in 1520 and explored it briefly before his expedition continued in his circumnavigation of the globe.

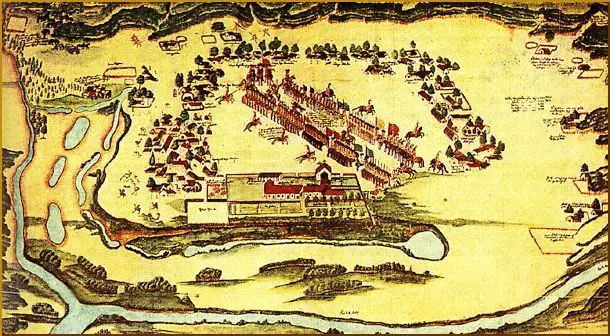

Between 1526 and 1529, the Italian explorer Sebastián Cabot conducted a detailed study of the estuary and explored the Uruguay and Paraná rivers. Cabot ascended the Paraná to the current city of Asunción, Paraguay, and also traveled a bit along the Paraguay River; in Asunción he obtained silver trinkets in exchange with the Guaraní Indians.

Several failed attempts to establish settlements on the southern shore of the estuary (notably near the current location of Buenos Aires), eventually led to explorations upriver and the founding of Asunción in 1537.

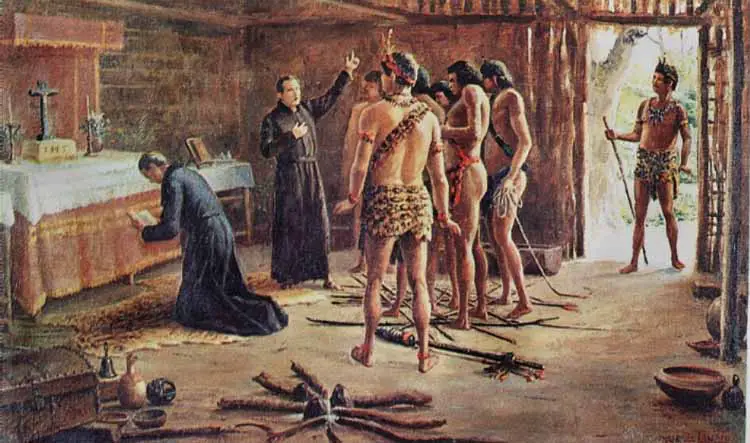

Buenos Aires was not re-founded until 1580. Around 1610 Jesuit priests had established the first of more than 30 missionary settlements that, until the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767, were the heart of what became known as the “Jesuit Empire.”

Some ruins of the missionary churches in the Argentinian province of Misiones and in eastern Paraguay are all that remain of this extraordinary company. Throughout the Spanish colonial era, the La Plata River remained a step backward to the empire.

The estuary of the La Plata River was practically closed to legal commerce, and Spain ignored the region until Portuguese and English ambitions threatened to expand in the estuary in the 1760s.

Economy of that era

The development of agricultural wealth, particularly in Argentina, resulted in a greater appreciation of the commercial value of these river systems after the mid-19th century. Beginning in the 1850s, thousands of German, French and Italian settlers settled along the lower Paraná River in the province of Santa Fe (see article: Purus River).

In the 1890s, German pioneers began carving agricultural settlements from forests along the Upper Paraná in Paraguay and Argentina. These people were followed by other Europeans and by a significant number of Japanese.

Wheat, beef, wool, cotton and skins began traveling thru the river and into the world trade in increased quantities from Argentina and Uruguay, while forest and tropical products and mate arrived from Brazil and Paraguay (see article: Río Segura).

The construction of the port made Buenos Aires more valuable as a seaport, and in 1902, similar improvements were completed in Rosario. Canal marking, surveys, dredging and other navigation aids became the responsibility of all coastal states.

Wars on the La Plata River

The navigation of the river system became a problem when the independent states of Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil and Bolivia were created within its course.

The British invasions of the La Plata River were a series of unsuccessful attempts to take control of the Spanish colonies located around the river basin. The invasions took place between 1806 and 1807, as part of the Napoleonic Wars, when Spain was an ally of France.

The invasions took place in two phases. A detachment of the British army occupied Buenos Aires for 46 days in 1806 before being expelled. In 1807, a second force occupied Montevideo, after the Battle of Montevideo (1807) and remained for several months, while a third force made a second attempt to take Buenos Aires.

The resistance of the local population and their active participation in the defense, without the support of the Spanish Kingdom, were important steps towards the May Revolution in 1810 and the Declaration of Independence of Argentina in 1816.

Territorial conflicts and restrictions on navigation caused several wars that culminated in the War of Paraguay (1864 / 65-70), in which Francisco Solano López led Paraguay in a disastrous fight against Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina.

In the twentieth century, other armed clashes occurred, mainly due to rumored oil wealth, which resulted in the El Chaco War (1932-35) that confronted Paraguay and Bolivia.

After several days of street fighting against the local militia in which half of the British forces in Buenos Aires were killed or injured, the British were forced to withdraw.

Why is it called La Plata River?

The modern name of the river was given by the explorer Sebastian Cabot who conducted a detailed study of the river and its tributaries in the 1520s. The name comes from the legendary Sierra del Plata, or “Silver Mountain”, which was thought to be upriver.

The legend has its roots in the 16th century when the castaways of the Juan Díaz de Solis expedition heard indigenous stories of a silver mountain in an interior region ruled by the so-called White King (see article: Caura River).

The first European who led an expedition in search of the mountain was Aleixo García, who crossed almost the entire continent to reach the Andean highlands.

On his way back to the coast, Garcia died when the natives ambushed him in Paraguay, but the survivors brought enough precious metals to corroborate their history and inspire others to embark on a similar expedition, all of which ended in failures.

La Plata River: Characteristics

The La Plata River behaves like an estuary in which fresh water and sea water are mixed. Its fresh water comes from the Paraná River, one of the longest in the world, and its main tributary, the Paraguay River, as well as the Uruguay River and other smaller streams.

The La Plata River receives the waters that drain from the Paraguay and Paraná river basins, which covers a large part of the southern center of South America; The total drained area is approximately 1.2 million square miles (3.2 million square kilometers).

Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay, is located on the northern shore of the estuary, and Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina, is located on the southwestern coast.

The Paraná Delta and the mouth of the Uruguay River are at the head of the Río de la Plata. The width of the estuary increases from the head to the sea.

With a distance of approximately 180 miles (290 kilometers), its 31 miles from the city of Punta Lara on the south coast (Argentina) to the port of Colonia del Sacramento in the north (Uruguayan shore), and 136 miles from shore to shore at the Atlantic end of the estuary (see article: Río San Francisco).

The La Plata River at its eastern part becomes much more than a river, because it has the biggest extension in the world, with a total area of approximately 13,500 square miles.

A submerged shoal, the Barra del Indio, acts as a barrier, which divides the Río de la Plata into an internal freshwater river area and an outer brackish estuarine zone.

The bank is located approximately between Montevideo and Punta Piedras. It is the fresh water of the inner area that causes many to describe the La Plata River as a river.

The upper river contains several islands, including Oyarvide Island and Solís Islands in Argentine waters and Juncal Island, Islote el Matón, Martín García Island and Timoteo Domínguez Island in Uruguayan waters. Due to the deposition of sediments from the heavy current load transported from the tributaries of the river, the islands in the La Plata River generally grow over time.

Tributaries of the La Plata River

The tributaries of the La Plata River are the Paraná River, and the Paraguay River (which is an important tributary of the Paraná) and the Uruguay River.

The tributaries of the Paraná River include the Paranaíba river, the Grande river, the Tiete river, the Paranapanema river, the Iguazú river, the Paraguay river and the Salado river, and it ends in the great Paraná delta.

The Paraguay River flows through the Pantanal wetland, after which its main tributaries include the Pilcomayo River and the Bermejo River, before it ends in the Paraná.

The main tributaries of Uruguay include the Pelotas River, the Canoas River, the Ibicuí River and the Negro River. Another important tributary to the La Plata River is the Salado del Sur River.

The Paraná River with its tributaries forms the largest of the two river systems that flow into the La Plata River.

The Paraná, which means “father of the waters” in the Guaraní language, measures 3,032 miles (4,880 kilometers) long and extends from the confluence of the Grande and Paranaíba rivers in southern Brazil to the southwest, the largest part of its course before turning southeast and draining in the La Plata River.

The Paraná is usually divided into two segments: the Alto (Superior) Paraná above the confluence with the Paraguay River and the Parana itself (or Paraná inferior) below the confluence.

The La Plata River is a salt estuary. Salt water, being denser than fresh water, penetrates the estuary thru a layer below the fresh water, which floats on the surface.

Salinity fronts, or haloclines, form at the bottom and on the surface, where fresh and brackish waters are found. Salinity fronts are also picnocline due to discontinuities in water density. They play an important role in the reproductive processes of fish species.

Physiography of the Paraguay basin

In Paso de Patria, on the right side (Paraguayan), the Paraná receives its largest tributary, the Paraguay River. This, the fifth largest river in South America its 1,584 miles (2,550 kilometers) long.

The name Paraguay River name, also taken from the Guaraní language, could be translated as “river of umbrellas (colored birds, feathers)” or “river of escarapelas”, an allusion, perhaps, to the feather headdresses that the riverside towns once carried .

The Paraguay also goes thru southern Brazil, in the central plateaus of the state of Mato Grosso, at an altitude of 980 feet above sea level. There it becomes navigable for small boats, about 150 kilometers downstream, near Cáceres, Brazil. After its confluence with the Sepotuba River, it is 275 feet wide and 20 feet deep.

Another 20 miles downstream, where the Jauru River joins it at a height of 400 feet, The Paraguay enters the Pantanal, a large seasonal swamp that covers much of southern Mato Grosso and northwestern Mato Grosso del Sur state.

During the dry season (from May to October), the swamps of the Pantanal are reduced to small patches of marshland. With the onset of rains in November, the slow-flowing rivers fill up quickly to their capacity, and a large and shallow lake is formed.

The Spanish missionaries confused it with a permanent lake, and it appeared as “Lake Xarays” in the first maps of the region.

The main canal of the Paraguay borders the entire western edge of the Pantanal on a bed of sand, which flows around the many islands in its course. During its passage through the Pantanal, the river receives tributaries as important as the Cuiabá, Taquari and Miranda rivers.

About 470 miles downstream, it flows from north to south at the border between Brazil and Paraguay before joining a tributary, the Apa River, which flows from the east and demarcates part of the Brazilian-Paraguayan border.

The river then enters Paraguay, after having traveled about 640 miles from its origin. After traveling more than 200 miles in Paraguay, the Pilcomayo River joins the border with Argentina, near Asunción.

It then flows south-southwest along the Argentine-Paraguayan border for about 140 miles, until it joins on its west bank with the Bermejo River. Continuing along the border for another 40 miles, then it flows into the Paraná River a short distance from the Argentine city of Corrientes.

From its confluence with the Apa, 630 miles to its mouth, the Paraguay river extends over a shallow and wide bed, with an average width of about 2,000 feet. To the south of Asunción, the right bank of the river (Argentina) descends gradually while its left bank at the Paraguayan side rises, forming cliffs.

Along this stretch, floods develop mainly on the western shore, extending over the Argentine plain for distances of three to six miles. These lands are part of the Gran Chaco.

Physiography of the Alto Paraná basin

The Rio Grande rises in the Sierra da Mantiqueira, part of the mountainous interior of Rio de Janeiro, and flows west for approximately 680 miles; but its numerous waterfalls, such as Marimbondo Falls, with a height of 72 feet (22 meters), make it useless for navigation.

The Paranaíba, which also has numerous waterfalls, is formed by many tributaries. The northernmost one is the San Bartolomeo River, which rises just east of Brasilia.

From its origin in the Grande-Paranaíba confluence to its confluence with the Paraguay, about 750 miles down the river the Alto Paraná receives many tributaries from both sides.

The three most important tributaries – the Tiete, Paranapanema and Iguazu rivers – join Alto Paraná on their left bank and have their birth places a few kilometers from the Atlantic coast of Brazil.

Alto Paraná first flows in a southwest direction through a deep neckline on the southern slope of the former Brazilian Sierra, whose configuration determines its course.

Just before starting its path along the border between Brazil to the east and Paraguay to the west, the river must cross the Sierra de Maracaju (Mbaracuyú), which in the past served as a natural dam, to the Itaipu hydroelectric dam.

The dam project was completed there in 1982; The River once expanded its bed in a lake 2.5 miles wide and 4.5 miles long, with Guaíra, Brazil, standing on the southern shore. The passage of the river through the mountains was, until 1982, marked by the Guaira Falls (Salto das Sete Quedas), which had eight times the volume of water of the Niagara River of North America.

Since the completion of the first stage of the Itaipu Dam project, the falls and the lake have submerged, and a reservoir now extends upstream for about 120 miles and covers more than 700 square miles.

The Iguazú River (Iguazú meaning “Great Water” in Guaraní language) joins the Alto Paraná at the point where Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina converge. Growing in the Sierra del Mar, near the Brazilian city of Curitiba (which is why it is sometimes called Rio Grande de Curitiba), the Iguazu flows about 380 kilometers from east to west, where about 70 waterfalls reduce the elevation of the river by a total of approximately 2,650 feet.

While the Ñacunday Falls are 131 feet high, the spectacular Iguazu Falls, on the border between Brazil and Argentina, 14 miles upstream from the Iguazú-Alto Paraná confluence, have a height of approximately 270 feet, almost 100 feet more high than Niagara Falls.

As the river approaches the falls, it widens before falling over the crescent-shaped edge, producing horseshoe-shaped falls more than two miles wide.

Under the falls, the river passes several miles through a gorge (Garganta del Diablo, literally, “Devil’s Throat”) that is only 164 feet wide with heights varying from 65 to 328 feet.

From the confluence of Iguazu to its union with the Paraguay River, Alto Paraná continues thru the border between Paraguay and Argentina.

As long as it is flanked on the left bank (Argentina) by the steep edge of the Sierra de Misiones, the river advances in a southwest direction, but is repeatedly twisted from side to side on a rocky bed studded with outcrops of porphyry basalt.

In Posadas, Argentina, where it is approximately 1.5 miles wide, the river turns sharply to the west and begins a more winding course, covering islands of considerable size and frequently punctuated by rapids and basalt outcrops that hinder the navigation. In the Apipé Rapids, the river is only between 4 and 6 feet deep.

Physiography of the lower Paraná basin

After it merges with the Paraguay, the combined current of the Paraná turns south as it passes through Corrientes. Now it becomes a typical “plains” river, with its proper characteristics and an extensive flood plain on its right bank, with extensions up to 24 miles wide subject to flooding.

Its permanent bed, approximately 2.5 miles wide in Corrientes, narrows to about 8,000 feet in Bella Vista, about 7,000 feet in Santa Fe, and about 6,000 feet in Rosario, and is covered with islands. Santa Fe, on the right bank in front of the port of Paraná, is where the Paraná River receives its last important tributary, the Salado River.

Then, between Santa Fe and Rosario, the right bank begins to rise as the river surrounds the edge of the undulating plain, which flanks it to the delta, and reaches altitudes ranging from approximately 30 to 65 feet.

The left margin, meanwhile, is always higher than the right, but it has to withstand the erosive action of water, which becomes increasingly murky as large masses of land constantly fall into it; In the delta, the main branch of the river runs along a break in the terrain, with its left bank consisting of a cliff about 75 feet high.

The Paraná Delta has its apex as far north as Diamante, upstream from Rosario, where branches of the river begin to turn southeast. About 11 miles wide at its upper end, the width of the delta grows to approximately 40 miles at the mouth of the river.

There, the separated branches of Paraná flow into the Río de la Plata, about 200 miles from Diamante. With an area of 5,500 square miles, the delta is constantly advancing, as 165 million tons of alluvial deposits flow annually.

Within the delta, the river is divided again and again into branches, the most important being the last two major canals, the Paraná Guazú and the Paraná de las Palmas. The islands of the delta, of alluvial origin, are of low height and of variable size.

Its banks and the outer fringes of the river have protective embankments covered with trees, but nevertheless they can be submerged in times of flooding, when they have the appearance of flooded forests.

Physiography of the basin of the Uruguay River

The Uruguay River is other main river system with 990 miles (1,593 kilometers) in length, which flows into the La Plata River. Like Alto Paraná and Paraguay, the Uruguay River originates in southern Brazil, formed by several small streams that rise on the western slope of the Sierra del Mar.

From the south, the Pelotas River joins, which divides the states of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina. After flowing westward, the Uruguay turns southwest in its union with the Peperi Guacu River, the first major tributary that joins it from the north.

For most of its course, the fast flowing Peperi Guacu marks the limit between the Argentine province of Misiones and Brazil; and after its confluence with the Uruguay, the latter river divides Brazil and Argentina.

A few kilometers beyond the confluence with the Peperi Guacu, the river is contracted between the rocky walls of the Grande Falls, a two-mile stretch of rapids with a total descent of 26 feet in 8 miles. At this falls, the river suddenly narrows from 1,500 feet to a minimum of 100 feet.

Several small rivers join the Uruguay from the west and are navigable in their lower parts using canoes and small boats. The main rivers that join from north to south are, Aguapey, Miriñay, Mocoretá (which divides between Rivers and Currents) and Gualeguaychú.

The most important tributaries of the Uruguay however come from the east. The Ijuí, Ibicuí and Cuareim are short rivers but of considerable volume; the latter is part of the border between Brazil and Uruguay.

At the mouth of the Cuareim, Uruguay becomes the dividing line between Argentina and Uruguay, and flows almost directly south. A dam on the falls in Salto, Uruguay, forms the Salto Grande reservoir about 40 miles upriver.

The Río Negro, approximately 500 miles in length is the largest tributary of the Uruguay, joining the latter only 60 miles from the La Plata River. the Negro River rises on the border with Brazil in the state of Rio Grande do Sul and flows west through the center of Uruguay.

Like the Alto Paraná, the Uruguay River is generally clear and has little sediment, except in seasonal floods. After its union with the Negro, the Uruguay widens sharply to a width of 4 to 6 miles and becomes a virtual extension of the La Plata River estuary.

System hydrology

The speed of the Paraná River current changes frequently during its long course (see article: Tocantins River). For the Alto Paraná, the speed decreases when the bed widens (especially when a real lake is formed, as in the Itaipu dam) and grows much faster where the bed narrows (as in the canyon downstream of Itaipú).

Further down the river, loses speed on its way to Posadas, but then accelerates through a series of rapids. It becomes slower again downstream of Corrientes, stabilizing its flow at an average speed of 2.5 miles per hour on the road to the La Plata River.

Along the Paraguay River basin, which covers more than 380,000 square miles, the elevations rarely exceed 650 feet above sea level. Therefore, for a long distance, the gradient of the river varies only slightly, from approximately 0.75 to 1 inch per mile (1.2 to 1.6 centimeters per kilometer).

The various streams of the basin have low banks or natural dikes, which are formed when sediment is deposited along the slow-flowing parts of the river canal during the flood phase.

When the river recedes, its banks remain high above the level of the neighboring plains. During floods, a continuous water table, often up to 15 miles wide, underlies the flooded plains, and about 38,600 square miles of surface is flooded.

The Paraguay has variable flow rates between its birth and the confluence with the Paraná. Above Corumbá, in Brazil, it has a typically tropical characteristic, beingt its highest point in February and in the lowest from July to August. Below Corumbá, the highest point occurs in July and the lower point from December to January.

The volume of the low Paraná River is related, for practical purposes, to the amount of water it receives from the Paraguay, which supplies about 25 percent of its total. High periods normally occur between November and February and low periods in August and September.

An important factor in the hydrological regime of the Lower Paraná is that the Alto Paraná and the Paraguay reach their maximum flow at different times. While the Alto Paraná mountain basin drains so quickly that water begins to rise in Corrientes in November, reaching its maximum height there in February, the swamps of the Pantanal of the upper basin of Paraguay retain precipitation much longer. This means that the high waters of the Paraguay do not reach Corrientes until May, reaching its peak in June.

Therefore, the levels in the lower Paraná begin to sink in March, rise from May and again sink from July to September.

When the Alto Paraná and the Paraguay reach their highest levels at the same time, the Lower Paraná has to transport an exceptionally heavy volume of water, as it did in 1905, when the delta experienced heavy flooding.

Height of the La Plata River now

The average total volume of the river in the La Plata River is approximately 610,700 cubic feet (17,293 cubic meters) per second, being its highest recorded volume 2,295,000 cubic feet per second (1905) and the lowest 86,400 (1945).

Tides of the La Plata River

The currents in the La Plata River are controlled by tides that reach their source and beyond, to the Uruguay and Paraná rivers. Both rivers are influenced by tides for approximately 190 kilometers (120 miles).

The tidal ranges in the La Plata River are small, but their wide width allows a tidal prism important enough to dominate the flow regime despite the large discharge received by the tributary rivers.

What is the depth and where is the mouth of the La Plata River?

The depth of the La Plata River varies from 6 feet above the sandbars to 65 feet in the intermediate canals, reducing along the south coast.

The depth of the internal river area is between 1 and 5 meters (3.3 to 16.4 feet). It is approximately 180 kilometers (110 miles) long and up to 80 kilometers (50 miles) wide. The depth of the external estuary area increases from 5 to 25 meters (16 to 82 feet).

Location and map of the La Plata River

On the map of the La Plata River we can see that it is part of the border between Argentina and Uruguay, with the main ports and capitals of Buenos Aires and Montevideo on its western and northern coasts, respectively. The coasts of La Plata River are the most densely populated areas of Argentina and Uruguay which increases the navigability as can be seen on the nautical map of the La Plata River.

Where is the La Plata River born?

The question of where is the La Plata River born? is asked a lot. The answer is that it has its beginning at the confluence of two smaller rivers, has an elongated shape and flows into the Atlantic.

Limits of the La Plata River

The river is approximately 290 kilometers (180 miles) long, and widens from approximately 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) at its origin to approximately 220 kilometers (140 miles) at its mouth.

What countries cross the La Plata River?

It is part of the border between Argentina and Uruguay, with the main ports and capital cities of Buenos Aires in the southwest and Montevideo in the northeast. Martín García Island, off the coast of Uruguay, is under Argentine rule.

La Plata River in Chile

This steep stream of low height and low volume enters the Villarica Lake, just in front of Pucón. It only happens during in the spring or after an intense and prolonged summer storm. On some maps, such as the one showing the Lake Caburgua, it is also known as the Quilque River.

The stream is a narrow and deep canyon with multiple large falls being the tallest in the range of the 10 meters.

Soils

The two contributory river systems reduce an immense amount of sediment each year (see article: Amazon River). The turbidity of the water in the La Plata River in Argentina is increased by the tides and winds that make it difficult to deposit silt in the bed.

When the sediments settle, the mineral and organic matter form large banks such as Playa Honda Shoal that is right next to the Paraná Delta, the Ortiz and Chico banks downstream, and the banks of Rouen, English, German and Archimedes that can be found even further.

The Argentine estuary coast is low; its shores are form of marine debris and coarse sand, and the coast is subject to flooding in some places. Entrances to Argentine ports (including Buenos Aires) require constant dredging.

The Uruguayan coast is considerably higher and consists mainly of rocks and dunes. In front of the Uruguayan coast there are several small islands, such as Hornos, San Gabriel, López, Lobos and Farallón.

Contamination of the La Plata River

The contamination from the cities and agricultural areas has led some to label the La Plata River and its small tributaries as the “worst environmental disaster” in Argentina.

It is common to see garbage and sewage water floating along the river. Although the Argentine Supreme Court requested an official plan to clear the riverbed in 2008, little has been done.

For example, in 2008 there were 141 open dumps with industrial, chemical and household wastes along the Matanza tributary, which runs from western Buenos Aires to the Río de la Plata.

According to the cleaning plan, the dumps were supposed to be closed by 2010, but 207 others had been reported instead bringing the total number of dumps to 348.

In addition to garbage and chemical loads from urban sources, increases in the use of fertilizers on the farmland that border the river have increased the microcystins and the eutrophication (the process by which nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer cause proliferation of algae that deprive oxygen of another aquatic life).

This is very worrying because many areas, including the City of Buenos Aires, get their drinking water from the La Plata River. It will be very interesting to know how many governments with vested interests in the La Plata River respond to the current environmental problems that plague it.

Like the problem of global climate change, the problem of contamination through a multinational river system will require several countries and different groups to work together. Hopefully, for the sake of the leatherback’s turtle survival and human health, this difficult goal will be met.

Plant life

Plant life within the vast region of the La Plata River is very diverse (see article: Putumayo River). To the east, in the upper Parana basin, and at the highest elevations, there are forests with valuable evergreens, such as the Paraná pine, which is used as softwood.

The western region is mainly grassland used for grazing cattle. In flooded areas there are plants that thrive in wetlands such as the beautiful water hyacinth, the Amazon water lily, the trumpet tree and the guama.

Along the rivers and streams there are palm trees such as the muriti and carandá and several species of quebracho, trees valued as a source of tannin. In the Gran Chaco, the western region of the Paraguay where the land is used primarily for livestock, there are groups of trees and shrubs and herbaceous savannas, along with thorny drought-tolerant shrubs.

Throughout the eastern Paraguay there are lapachos and evergreen shrubs, whose leaves are used to make mate, a stimulant drink similar to tea popular in many South American countries.

La Plata River fauna

The La Plata River in Argentina is a habitat for the rare Dolphin of La Plata and several species of sea turtles:

- Caretta caretta.

- Chelonia mydas.

- Dermochelys coriacea.

The La Plata River has a large diversity of animal life, including some very distinctive species. Silver dolphins can be found along the estuary of the river and throughout the Atlantic coast as well as whales.

This is the only dolphin that inhabits freshwater and salt water estuaries. Also, this is the only river that does not exclusively contain freshwater ecosystems. The silver dolphin also has the longest (proportionally) peak of all cetaceans.

The species is listed as ‘vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species, being its main threats accidental catch in fishing gear, as well as coastal fishing, traffic and pollution of industrial development.

Fishing in the La Plata River

In 2010, a baby dolphin from La Plata was found and released on a beach near Montevideo, in Uruguay. It had suffered injuries probably caused by a fishing net, which led to a broader understanding of the status of the species.

The many species of fish include:

- Catfish.

- Surubí.

- Manduva

- Patí.

- Pacu.

- Corbina

- Pejerrey.

- Meat eating Piranhas.

- Goldfish.

There are also a large number of reptiles throughout the region, such as:

- Two species of alligators.

- Iguana lizards.

- Rattlesnakes

- Water boas.

- Yararás.

- Frogs

- Toads

- Freshwater crabs

Also, the area is populated with numerous birds, herons and storks as well. The La Plata River also hosts three different species of sea turtles: the sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), the loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) and the leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea).

Sadly, these turtles are also victims of bycatch, and the green and loggerhead turtles are in danger, however, the leatherback turtles are the ones most critically endangered. Leatherback turtles are distinguished by their long-distance migratory movements, and there is a documented case of a leatherback turtle that traveled all the way from Benin (Africa) to Uruguay.

Pejerrey on the La Plata River

The Pejerrey is a thin fish but with a rounded belly (not sharp); with a short head; big eyes; and small mouth, barely open in the front and very oblique.

Both the head and the body are covered with large scales. The first dorsal fin (3 to 7 spines) is smaller than the second and originates midway between the tip of the snout and the base of the caudal fin, the second dorsal has 7 to 10 soft rays and originates in the middle of the anal.

Weather

As for the climate, the La Plata River has as a characteristic that in the area of the northern basin it has a generally warm and humid weather with rainy summers (from October to March) and especially dry winters (from April to September). More than 80 percent of the annual rainfall occurs in summer with torrential rains often accompanied by hail.

The annual amount of precipitation is 40 inches in the western lowlands to 80 inches in the eastern mountainous region. Temperatures in the upper basin range from a minimum of approximately 37º to a maximum of 107º and an annual average of 68º or higher.

The middle and lower basins have subtropical to temperate climate and maintain a humidity level of 70 percent. Precipitation is somewhat lower than that of the upper basin, however it rains throughout the year. The average rainfall along the entire La Plata River is 44 inches.

Tromba of the La Plata River

The tromba of the Río de la Plata happened on January 28, 1988, when a great storm affected vast areas of the La Plata River and bordering areas of Argentina and Uruguay.

People

Wandering the Alto Paraná and Paraguay rivers and throughout the Pantanal were once nomadic hunter-gatherers known as the Bororo and Guayacurú people. Further south, the Guarani established more permanent villages where they raised crops such as corn and cassava (mandioca), which are still the main commodities in the region today (see article: Columbia River).

The Great Chaco of western Paraguay and the Pampas of Argentina was home to the nomads Lengua and Abipón.

Due mainly to the extensive loss of the male population of Paraguay during war times, the Spaniards and Portuguese mixed with the indigenous women, creating a population of mostly mestizos.

Unlike most other countries, 90% of Paraguay’s population speaks the Guaraní language along with Spanish. In Brazil, however, many of the indigenous tribes have remained intact and somewhat isolated.

Other groups such as the Boror, Bacairi and Tereno have adopted Brazilian culture and even some Christian traditions. There are also a significant number of descendants of German and Japanese immigrants living in the Alto Paraná region of Brazil.

Today the majority of the population in the La Plata River region lives in Buenos Aires, Argentina and Montevideo, Uruguay, and is mainly of European origin.

Language

The adoption of the Spanish language in the area was due to Spanish colonization in the region. Many people who do not speak Spanish confuse Rioplatense Spanish with Italian because of the similarity of their cadence. However, native Spanish speakers can understand it as another form of standard Spanish, as different from Peninsular Spanish as Mexican or Caribbean.

Until immigration began in the region, the language of the Río de la Plata had virtually no influence from other languages and varied mainly through localisms. However, Argentina, like the United States and Canada, consists mainly of immigrant populations, the largest being of people of Italian descent.

Due to their diverse immigrant populations, several languages influenced the Spanish Creole of the time:

- 1870-1890: mainly speakers of Spanish, Basque, Galician and Northern Italian and some from France, Germany and other European countries.

- 1910-1945: once again Spanish, southern Italian and in smaller numbers from all over Europe; Jewish immigration, mainly from Russia and Poland from the 1910s until after World War II, was also very important.

The English speakers, from Great Britain and Ireland, were not as numerous as the Italians, but they had an influence on the upper classes, industry, business, education and agriculture.

The indigenous languages in the area have been influenced, or even completely replaced, by Spanish since most of the indigenous populations were expunged when the Spaniards arrived in Argentina. However, some of those words have entered the Spanish language from the region, and some have been adopted even in English.

Current economy

The La Plata River is very important economically for the countries within its basin. Estuary crops are the most important resource. Aldo, the estuary is the main fishing location in the region.

Hydroelectric plants within the estuary region provide energy to the area. The rivers that flow into the estuary are the main water resource for the most densely populated regions of South America.

A treaty between Argentina and Uruguay was established in 1973 to administer the binational estuary. On the Uruguayan side, limited management has been developed with financial and technical assistance from the International Development Research Center (IDRC) of Canada.

Its objective for this area is to improve environmental conditions while promoting the sustainable use of coastal resources. This experiment, called ECOPLATA, requires the combined efforts of national and local institutions.

Some of the economic and ecological challenges are based on the fact that approximately 70 percent of the 3.3 million inhabitants of Uruguay live within 62 miles (100 km) of the coast.

How contaminated is the La Plata River?

Unfortunately, human activities cause marine contamination and can accelerate the erosion of beaches and dunes. Mechanized agriculture and deforestation cause soil erosion, which then leads to sedimentation.

Coastal degradation is also due to inappropriate sand extraction activities. With all these concerns combined with the rapid depletion of fish, it is not surprising that the deterioration of the ecosystem is affecting both local populations and the tourist industry.

On the Argentine side, located on the western shore of the estuary of the La Plata River facing Uruguay, is the cosmopolitan entrance to South America, Buenos Aires. Its port is the largest in South America and handles 96 percent of the country’s maritime traffic.

The Buenos Aires Port cruise terminal opened in 2001, contributing to congestion. With its narrow canal from the port to the Atlantic Ocean, there is a need for constant dredging to maintain the flow of heavy traffic. The cleanliness of the waterways remains one of the most pressing problems in the city.

La Plata River, the widest in the World

Just east of the port in Buenos Aires there is an ecological reserve called Costanera Sur Ecological Reserve. Built on a landfill with wetlands full of pampas grass, there are more than 500 species of birds and some iguanas which make the area special for nature lovers.

A major threat to the estuary of the La Plata River is the arrival of small mollusks from Asia and Africa transported as larvae in bilge water that ships take in several ports to improve their stability. When the ship enters shallow waters, such as the La Plata River, the water is discharged and poured into a new ecosystem. Adult species enter the ship’s hull, chains or keel.

The most harmful of these species is the golden mussel, a freshwater mollusk native to the basins of the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Without natural predators, this new intrusive specie can displace existing life classes and prevent the normal development of swamp plants and change local ecological conditions.

The solutions to these problems are found in a collaborative network for research, development and implementation of an integrated plan to preserve and develop coastal resources and ecosystems.