Last Updated on August 29, 2023 by Hernan Gimenez

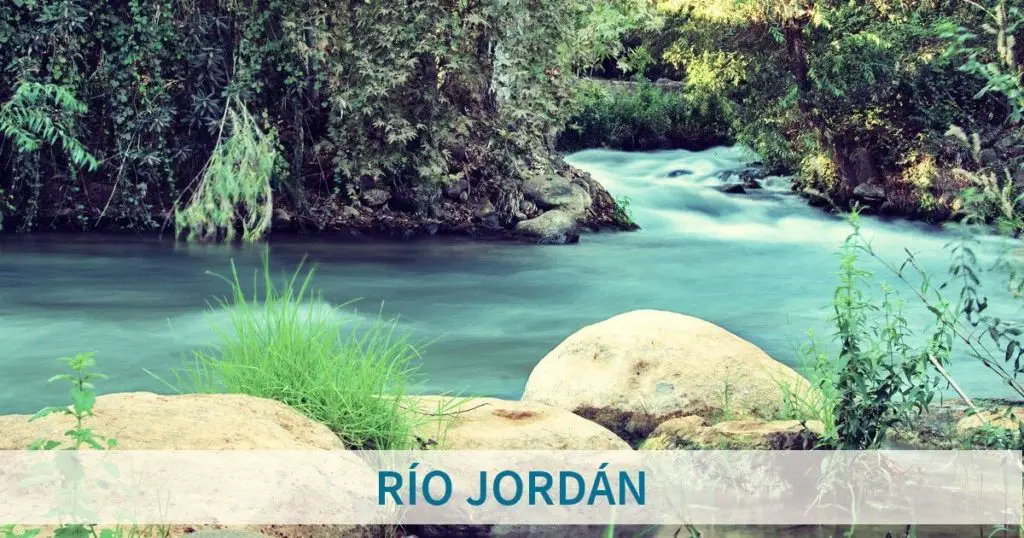

Jordan River, Arabic Nahr Al-Urdun, Hebrew Ha-Yarden, river in southwestern Asia, in the Middle East region. It lies in a structural depression and has the lowest elevation of any river in the world.

Indice De Contenido

History of the Jordan River

The ancient Jordan River and the Dead Sea were explored by boat in the 19th century, most notably by Christopher Costigan in 1835, Thomas Howard Molyneux in 1847, William Francis Lynch in 1848 and John MacGregor in 1869.

The full text of W. F. Lynch’s 1849 book, Narrative of the United States Expedition to the Jordan River and Dead Sea, is available online.

In 1964, Israel began operating a pumping station that diverts water from the Sea of Galilee to the National Water Carrier (see article: Hueñu Hueñu River).

Also in 1964, Jordan built a canal that diverts water from the Yarmouk River, another major tributary of the Israeli Jordan River, to the East Ghor Canal. Syria has also built reservoirs to capture the Yarmouk’s water. Environmentalists blame Israel, Jordan and Syria for extensive damage to the Jordan River ecosystem.

In modern times, i.e. today’s Jordan River, 70% to 90% of the water is used for human purposes and the flow is significantly reduced.

As a result of this and the high evaporation rate of the Dead Sea, as well as the industrial extraction of salts through evaporation ponds, the sea is shrinking. All the shallow waters at the southern end of the sea have been drained in modern times and are now saline.

A small section of the northernmost part of the Lower Jordan, the first ca. 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) below the Sea of Galilee, has remained pristine for baptism and local tourism.

The most polluted stretch is the 100 kilometres (62 miles) downstream, a meandering river from its confluence with the Yarmouk to the Dead Sea (see article: Red River).

In 2007, Friends of the Earth Middle East (FoEME) named the Jordan River as one of the world’s 100 most endangered ecological sites, in part because of a lack of cooperation between Israel and neighbouring Arab states.

The same environmental group said in a report that the Jordan could dry up by 2011 if the deterioration is not halted. The Jordan River once flowed at a rate of 1.3 billion cubic metres a year; by 2010, only 20 to 30 million cubic metres a year flowed into the Dead Sea.

In comparison, the total amount of desalinated water produced by Israel in 2012 was estimated to be about 500 million cubic metres per year (see article: Tula River).

Recent literature highlights the role of power asymmetries, discourses and narratives in shaping hydropolitics along the river basin.

Characteristics of the Jordan River

One of the characteristics of the Jordan River is that it is more than 223 miles (360 km) long, but because of its meandering course, the actual distance between its source and the Dead Sea is less than 124 miles (200 km).

After 1948, the river marked the border between Israel and Jordan from the southern Sea of Galilee to the point where the Yābis River flows from the eastern shore (left).

However, since 1967, when Israeli forces occupied the West Bank (i.e. the territory on the west bank of the river south of its confluence with the Ybis), the Jordan River has served as a ceasefire line as far south as the Dead Sea (see article: River Son).

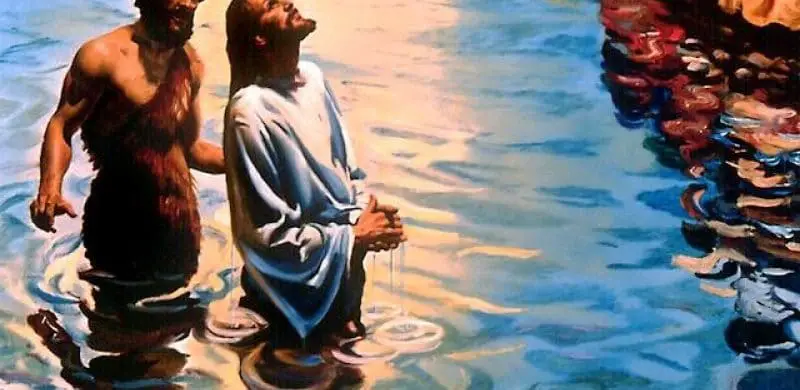

The river was called Aulon by the Greeks and is sometimes called Al-Sharī’ah (“Place of Irrigation”) by the Arabs. Christians, Jews and Muslims all revere the Jordan. It was in its waters that Jesus was baptised by St John the Baptist. The river has remained a religious destination and a place of baptism.

The Jordan River has three main sources, all of which rise at the foot of Mount Hermon. The longest of these is the Ḥāṣbānī, which rises in Lebanon, near Ḥāṣbayyā, to a height of 1,800 feet (550 metres).

From the east, in Syria, flows the Bāniyās River. Between the two is the Dan River, whose waters are particularly cool (see article: Colorado River).

Just inside Israel, these three rivers meet in the Hula Valley. The plain of the Hula Valley was originally occupied by a lake and marshes, but in the 1950s some 23 square miles (60 square km) were drained to create agricultural land.

By the 1990s, much of the valley floor had been degraded and parts of the area were flooded.

It was decided to preserve the lake and surrounding wetlands as a nature reserve, and some of the plants and animals (especially migratory birds) have returned to the region.

At the southern end of the valley, the Jordan has cut a gorge through a basalt barrier. The river drops sharply to the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee.

This lake, historically measured at 686 feet (209 metres) below sea level, has averaged about 6.5 to 13 feet (2 to 4 metres) less than that annually for decades.

However, the lake helps to control the flow of the river. Leaving the southern shore of the lake, the Jordan receives its main tributary, the Yarmouk River, which forms part of the Syrian-Jordanian border. It is then joined by two other tributaries, the Ḥarod on the right bank and the Yābis on the left. The plain of the Jordan extends to a width of about 15 miles (24 km) and becomes very regular.

The flat, barren terraces of this area, known as the Ghawr (Ghor), are cut here and there by riverbeds or rivers into rocky towers, pinnacles and wastelands, forming a maze of ravines and sharp ridges that resemble a lunar landscape.

The valley that the Jordan has carved into the plain is between 1,300 and 10,000 feet (400 and 3,000 metres) wide and 50 to 200 feet (15 to 60 metres) deep (see article: Caqueta River).

Along this stretch, the Jordan floodplain is known as the Zūr, and it meanders so much that although it runs for about 135 miles (215 km), it covers an area of only 65 miles (105 km) between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea of Galilee.

The frequently flooded Zūr used to be covered with thickets of reeds, tamarisk, willows and white poplars, but since the dams were built to control the flow of the river, this land has been converted to irrigation. This land has been converted into irrigated fields. Finally, the Jordan flows through a wide, gently sloping delta into the Dead Sea.

Although the surrounding plateaus receive relatively abundant rainfall, the Jordan Valley is not well watered.

The Ḥula Valley receives about 22 inches (550 mm) a year, while only about 3 inches (75 mm) falls north of the Dead Sea.

Winters along the river are mild, especially in the south, but summers are hot, again increasingly southerly.

The Jordan River in Israel is fed by rainfall from the neighbouring highlands; the water flows downstream as rivers or streams (see article: St Lawrence River).

The Jordan itself is shallow. Its high water period lasts from January to March, while its low water period occurs in late summer and early autumn.

The flow is relatively fast and the river carries a considerable load of silt. However, the flow rate decreases downstream due to evaporation losses and seepage.

The inflow of the Yarmouk once nearly doubled the flow of the Jordan, but the Yarmouk’s contribution has been reduced by the construction of dams upstream.

The presence of hot springs, especially in the Tiberias region on the western side of the Sea of Galilee, and the concentration of gypsum give the Jordan a relatively high salinity, which can leave a salt residue on the ground when the water is used for irrigation.

12 Stones of the Jordan

The Jordan River in the Bible, beginning in 3:1 of the Book of Joshua, we are told that Joshua and the people set out from Shittim (acacia grove) until they reached the banks of the Jordan River (see article: Snake River).

The people follow behind the priests carrying the Ark of the Covenant; and as the priests’ feet enter the Jordan, the swiftly flowing waters stop and form a passage of dry land for them, vv. 13-15. And after they have crossed, the divine voice tells Joshua to take twelve stones from the waters of the Jordan and place them in the new land they have just entered, one large stone for each of the twelve tribes.

Joshua obeys and in addition twelve men take another twelve large stones from the new land and place them in the Jordan River, 4: 1 – 9. So, twelve stones were taken out of the river and another twelve were placed in it. What do these mysterious stones say?

One Jewish source links them to the Ten Commandments, because they too were written on stone tablets; and one Jew argues that Joshua did not receive specific instructions from God to place twelve stones in the river. Frivolous remarks like these deserve no comment. So what do the stones mean? Verse 4:6 comments on this very question, but only tells us that they were a memorial to Jesus dividing the waters of the Jordan, 4:7.

But there is something else, and the scholars seem to have missed it completely. Notice that v.18 very briefly repeats the account of the crossing of the Jordan, while v.19 adds that the people camped at Gilgal. Then v.20 provides a very significant fact: that the stones taken from the Jordan were deposited at Gilgal. After this, the question posed in verse 6, “What do these stones mean?”, is repeated in v. 21, with the same answer as before, except that v. 23, 24 adds a comparison with the crossing of the Red Sea.

Song of the Jordan

The Jordan River is a common symbol in popular, gospel and spiritual music, as well as in poetic and literary works.

Since, according to Jewish tradition, the Israelites made a difficult and dangerous journey from slavery in Egypt to freedom in the Promised Land, the Jordan may refer to freedom. The actual crossing is the last step of the journey, which is then complete.

Because of Jesus’ baptism, the waters of the Jordan are used for the baptism of heirs and princes in several Christian royal houses, such as the cases of Prince George of Cambridge, Simeon of Bulgaria and James Ogilvy.

The baptism of Jesus is referred to in a hymn by the reformer Martin Luther, “Cristo unser Herr zum Jordan kam” (1541), the basis for a cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach, Cristo unser Herr zum Jordan kam, BWV 7 (1724).

The Jordan River, especially because of its rich spiritual significance, has been the inspiration for countless songs, hymns and stories, including the traditional African-American spirituals and folk songs “Michael Row the Boat Ashore”, “Deep River” and “Roll. Jordan, Roll”.

It is mentioned in the songs “Eve of Destruction”, “Will You Be There” and “The Wayfaring Stranger” and in “Ol’ Man River” from the musical Show Boat.

Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash’s “The Far Side Banks of Jordan” on June’s Grammy-winning studio album Press On mentions the Jordan River as well as the Promised Land. The Jordan River is also the subject of the song of the same name by reggae roots artist Burning Spear.

Jordan River Map and Location

Where is the Jordan River? The Jordan River rises in the grasslands of Mount Hermon, on the border between Syria and Lebanon, and flows south through northern Israel to the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberius).

After leaving the sea, it continues south, dividing Israel and the Israeli-occupied West Bank to the west from Jordan to the east, before emptying into the Dead Sea. The Dead Sea area is the lowest place in the world, with an elevation of about 1,410 feet (430 metres) below sea level in the mid-2010s. Below is a map of the Jordan River.

The Jordan River Today

Due to climate change and pollution, the Jordan River is now almost dry. Israel and Jordan signed an agreement to reduce pollution and protect the river. They also agreed to undertake construction and facilities to restore water flow and improve natural ecosystems.

The Jordan Valley is part of the vast East African Rift System, a rift valley that runs north and south from southern Turkey across the Red Sea to East Africa.

The valley itself is a long, narrow trough, averaging about 6 miles (10 km) wide, but narrowing in places, such as at each end of the Sea of Galilee.

Along its course, the valley lies much lower than the surrounding countryside, especially in the south, where the surrounding land can rise some 3,000 feet (900 metres) or more above the river.

The valley walls are steep, rugged and barren, broken only by the gorges of the tributaries (seasonal watercourses).

Where irrigation allows, the Jordan Valley has been settled by Arab and Jewish farming communities.

Notable areas of settlement are the Ḥula Valley in the north; the chain of agricultural communities south of the Sea of Galilee in the West Bank.

Including Deganya, the oldest kibbutz (collective agricultural settlement) in Israel, established in 1909: Afriqim, Ashdot Ya’aqov and Hawwat Shemu’el; the area along the East Ghor Canal on the East Bank; and the Wadi Fari’ah area in the West Bank.

Navigation is impossible due to the steepness of the river’s upper reaches, the seasonal fluctuations in its flow, and the shallowness of its lower reaches.

The water of the Jordan River is particularly important for irrigation. For a long time, even in ancient times, the water was not used, except for a few oases in the surrounding foothills, such as Jericho, which used the water from the springs that fed the river.

The Ghor region was once arid, desolate and uninhabited, but the 43-mile (69 km) East Ghor Irrigation Canal was completed on the east bank in 1967, allowing the cultivation of oranges, bananas, vegetables and beets on the Jordanian side of the valley.

In Israel, in addition to draining parts of the Shula Valley and building a canal from the Sea of Galilee to Beth Shean, a water supply network has been built that allows 11.3 trillion cubic feet (320 million cubic metres) of water to be transferred from Jordan.

Water pumped annually to central and southern Israel. The diversion of water from the river by Israel and Jordan has significantly reduced the Jordan River’s flow to the Dead Sea and has been a major factor in the significant drop in the sea’s level since the 1960s.

Biblical significance of the Jordan River

Given that the Jordan plays a more important role in biblical narrative than it may have historically, it is difficult to describe the river’s place in history; it is perhaps more appropriate to speak of the river’s place in the writing of Israelite (i.e. biblical) history.

Most famously, in the Book of Joshua, after the Exodus from Egypt, Joshua led the Israelite refugees across the Jordan River into Canaan (Joshua 3-4).

This narrative of conquest became a key idea in the formation of the people of Israel and served as a recurring motif in Israelite literature.

Another example of the same theme of the significance of the Jordan River in the Bible is the crossing of the Jordan in Jacob’s journey to Paddan-Aram to live with his uncle Laban; see especially his reflection on his life in Genesis 32:10: “With my staff alone I crossed this Jordan, and now I have become two companies.

Although Jacob speaks these words as he crosses the Jabbok River (a small tributary of the Jordan) on his return from Paddan-Aram, this is probably intended to foreshadow Joshua’s similar statement during the conquest of Canaan ( Josh 4:22).

The importance of crossing the Jordan undoubtedly inspired the stories of Elijah and Elisha (see 2 Kings 2:1-14) and ultimately the ministry of John the Baptist on its banks (see Matthew 3:1, Matthew 3:13).

But the fords of the Jordan were not always places of peaceful unification for the people of Israel. We often read of battles at these fords (see Judges 3:28, Judges 7:24-25) or on the eastern bank of the river (Judges 8:4, 1Sam 11, 2Sam 10:17, 1Ch 19:17, 1Macc 5:24, 1Macc 9:42-49).

Sometimes we even read of disputes between the various Israelite tribes at the fords (see Judges 12: 5-6, 2Sam 20: 1-2).

The topography and climate of the valley through which the Jordan flows have played a decisive role in the settlement and political importance of the region.

This political importance has left its mark on the historical writing of the biblical text, which in turn influences the theological and symbolic significance of the area.

Jordan River in the Bible

Numerous references to the Jordan River appear in both the Old and New Testaments, indicating its biblical significance and holiness.

In fact, the Jordan is mentioned 175 times in the Old Testament and 15 times in the New Testament.

The word ‘Jordan’ comes from the Hebrew word ‘Yarden’ {ירדן) which means descending. This name is appropriate for the river that runs from the heights of Mount Hermon to the depths of the Dead Sea.

The Jordan flows through the land and history of the Bible, giving its waters a spiritual significance that sets it apart from other rivers.

The Jordan is significant to Jews because the tribes of Israel, led by Joshua, crossed the river on dry land to enter the Promised Land after years of wandering in the desert.

For Christians, it is significant because John the Baptist baptised Jesus in the waters of the Jordan. The prophets Elijah and Elisha also crossed the river on dry land, and the Syrian general Naaman was cured of leprosy after washing in the Jordan on his way to see Elisha.

Baptism in the Jordan River

This could be the place where John the Baptist baptised Jesus, in the River Jordan, on the east bank of a large bend in the river opposite Jericho.

A site less than 2km east of the river’s present course, in Wadi Al-Kharrar, has been identified as Bethany beyond the Jordan.

This is where John lived and was baptised, and where Jesus fled to after being threatened with stoning in Jerusalem.

Until the peace treaty between Jordan and Israel in 1994, the area was a Jordanian military zone. After clearing nearby minefields, the Jordanian government has opened the site to archaeologists, pilgrims and tourists.

Jordan’s new Baptism Archaeological Park contains the remains of a Byzantine-era monastery with at least four churches, one of which is built around a cave believed to be what ancient pilgrims called “the cave of John the Baptist”.

While the Jordanian site was inaccessible, a modern site commemorating Christ’s baptism has been established at Yardenit in Israel, at the southern end of the Sea of Galilee.

Maintained by a kibbutz, it is a popular place for Christian pilgrims to renew their baptismal promises or for new Christians to be baptised, often in white robes and fully immersed in the fresh waters of the Jordan.

Jesus and the Jordan River

The authenticity of this place is as pure as the testimonies of the Gospels, pilgrims and travellers who have visited this precious site.

Recent archaeological excavations and related studies have revealed the remains of five churches that were uniquely designed and built since the 5th century as memorials to the baptism of Jesus.

In addition, the mosaic map of the Holy Land depicts the site. Finally, there are the official letters sent to the Royal Commission by many church leaders from around the world.

This church was considered to be the most important commemorative church of St John the Baptist on the east bank of the Jordan.

Theodosius (530 A.D.) wrote that 5 miles north of the Dead Sea, at the place where the Lord was baptised, there is a single pillar and on the pillar there is an iron cross.

There is also the Church of St John the Baptist, built by the Emperor Anastasius: this church is very high, built over large chambers, because of the Jordan River when it overflows.

Although the pillar marking the place where the Lord was baptised has not yet been found, the archaeological and architectural remains correspond to what Theodosius described.

The Jordan River flows through a wide, arid valley between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea. The Jordan Valley has been inhabited for thousands of years, with palm and agriculture being the main crops. Archaeological excavations have also confirmed the report in 1Kg 7:46 (repeated in 2Ch 4:17) that the inhabitants of the region east of the river exploited iron ore deposits there.

In addition, like many rivers, the Jordan was a political boundary between Israel and neighbouring nations before the Assyrians annexed Israelite territory east of the Jordan in the mid-8th century BC (see 2Ki 10:32-33; 2Ki 15:29). The river also served as a boundary between the Israelite tribes themselves (see, for example, Numbers 32:19, Numbers 34:15).

This is true in both biblical and modern times; the river forms the border between Israel and the Palestinian territories in the west and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in the east. In ancient times, the river probably formed a significant barrier to travel and could only be forded at certain points. This restricted trade and movement across the river.