The ratchet was a large ship of medieval Europe in the 14th century, used for long-distance trade and occasionally for warfare. In this article we present the history of this type of ship, its characteristics, its first constructions and the improvements that were made to it.

Indice De Contenido

What is a ratchet?

The ratchet was a large ship used for long sea voyages in the late Middle Ages, particularly between the 14th and 17th centuries.

It was most developed in southern European countries at the height of their commercial and maritime expansion.

It is characterised by its high sterncastle, the structure at the stern above the main deck of the ship. See ship types for information on similar ships.

It also had a forecastle, at the front end of which was a bowsprit, which is the mast that comes forward and is inclined at the bow. It is also called the mast or rigging key.

The ratchet also had a low waist. It usually had a square-rigged rig, used in the past by sailing ships at the back, on the foremast or mainmast and on the mainmast, while on the mizzen it had a lateen sail, knife-shaped or triangular, designed to be driven by the wind.

The ratchet was not only the first to incorporate the structures of the castles into the hull, but it also contained all the basic elements of the rigging that would be used and developed over the following centuries.

In its most developed form, it was an ocean-going vessel, built with carved planking, large enough to be stable in heavy seas and to carry a large cargo and provisions needed for long voyages.

Portugal was one of the medieval countries that most frequently used the three- or four-masted ratchet, which was derived from the single-masted ratchet.

As the forerunner of the galleon, the ratchet was one of the most influential naval designs in history, and even though ships became more specialised in the centuries that followed, the basic design of this ship remained unchanged throughout this period.

Also learn about the world’s greatest ships. You’ll be amazed.

History of the ratchet

In the 14th century, Western Europeans were constantly venturing into the waters of the Atlantic to conquer new territories and trade in new and exotic goods.

The various companies involved needed a very reliable ship that could withstand the vastness of the sea and the violent storms it could bring, and at the same time carry enough cargo to make the voyage profitable.

The ratchet cargo ship was a cutting-edge design for its time, built in increasingly large sizes by shipbuilders in Spain, Portugal, France and other coastal nations.

The late Middle Ages saw the design of square-rigged ships with a rudder at the stern, suitable for sailing along the coasts of Europe, from the Mediterranean to the Baltic and later the Atlantic.

It was particularly prominent in the 14th century, created by the Portuguese to carry out their explorations of the seas.

It had a basic configuration consisting of a hull with a considerable draught, which in nautical terms refers to the vertical distance between a point on the waterline and the baseline or keel, including the thickness of the hull. It also had its masts and a large rectangular sail.

Given the conditions in the Mediterranean, it was used mainly for trading in its early forays, on a par with galleys and two-masted vessels, including caravels with their lateen sails.

These and similar types of vessel were well known to sailors and shipowners in general, but were mainly used by the Portuguese.

As the Portuguese extended their trade further south along the Atlantic coast of Africa during the 15th century, they needed larger, more durable and more advanced sailing vessels for their long oceanic adventures.

They gradually developed their own models of ocean-going ratchets by combining and modifying aspects of the ship types they were already familiar with from both the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, and by the end of the century they were widely used for inter-oceanic voyages.

Their advanced sail rigging allowed them to navigate better in the strong winds and waves of the Atlantic, and their hull shape and size allowed them to carry larger cargoes.

These ships, built by the Portuguese, were notable in that they could often carry more than 1,000 tonnes on their voyages to India, China and Japan.

In addition to the medium tonnage ships, some large carracks were built during the reign of John II of Portugal, but they did not become popular until after the turn of the century.

For the next 100 years, the Portuguese controlled the East Indies trade, sending a fleet to India almost every year to coincide with the monsoon winds.

A typical three-masted ratchet, such as the São Gabriel, could have six sails: bowsprit, foresail, mainsail, mizzen sail and two topsails.

Ratchets were also used by the famous Portuguese navigator Vasco de Gama on his first successful voyage, sailing directly from Europe to India via the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of the African continent.

In 1498, de Gama left Portugal with 170 men, 3 carracks and a caravel; he returned 22 months later with only 2 ships and 55 men. He had sailed 24,000 miles and spent 300 days at sea.

It was the longest ocean voyage ever undertaken in the age of exploration.

In the mid-16th century, the ratchet was replaced by the first galleons, which continued to be used until the mid-17th century because of their greater carrying capacity.

Some disadvantages

Initially, this type of ship had disadvantages due to its large size.

These included poor manoeuvrability and slowness. However, as time went on, these shortcomings were overcome by modifications and improved by technical advances.

Another aspect of the ratchet that needed to be improved was that, due to its large draught, which is the vertical distance between a point on the waterline and the base line or keel, including the thickness of the hull, it could only load and unload at deep sea or river ports that could handle such large vessels, or it had to be anchored at a certain distance from the coast.

Due to its small size and depth, this condition limited its ability to manoeuvre in coastal ports.

Another disadvantage of the ratchet in the Middle Ages was the high cost of its manufacture.

This was due to the fact that the European nation states of the time were only nominal in nature, being in reality feudal territories and so-called city-states, which had very few resources to build ratchets.

First constructions

The most important ratchets were of Portuguese, Venetian and Genoese origin. The Spanish had not yet become popular.

The first constructions include the gigantic warships of the 16th century, such as the Portuguese Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai, or the one that bore the same name as King Henry VIII, the creator of the Royal Navy, the Henry Grâce à Dieu of 1514, better known as “Big Harry”, and the Mary Rose of 1510, which would be reformed in 1536.

These were examples of ships that showed a certain extravagance and allowed the introduction of new technologies.

These particular ships included bronze cannons on several decks and their flat sterns, despite the imposing castles, were prototypes of future armed galleons.

The importance of other carracks is also recognised, such as the Charente of Louis XII of France, which had 300 pieces of artillery and 1,200 soldiers.

There is also the Portuguese carrack of St John Botafogo, which was the largest of its time and had 200 guns. It was used on the Day of Tunis in support of Charles V.

Other famous fortresses were

- São Gabriel, commanded by Vasco da Gama in the Portuguese expedition of 1498.

- Flor do Mar, which served in the Indian Ocean for more than nine years. In 1512, it sank under the command of Afonso de Albuquerque after the conquest of Malacca with a huge booty, becoming one of the mythical lost treasures.

- The Dauphine, Verrazzano’s ship that explored the Atlantic coast of North America in 1524.

- The Grande Hermine, in which Jacques Cartier first sailed the St. Lawrence River in 1535. It was the first European ship to navigate the river beyond the Gulf.

- San Antonio, personal property of King John III of Portugal, which was wrecked off Gunwalloe Bay in 1527 and whose salvage almost provoked a war between England and Portugal.

- Great Michael, a Scottish ship, the largest in Europe at the time.

- Peter Pomegranate, built during the reign of Henry VIII. Historians report that English military ratchets like this were once called ships.

- Santa Anna, a particularly modern design commissioned by the Knights Hospitaller in 1522 and sometimes hailed as the first armoured ship.

- Madre de Deus, seized by the Royal Navy off the island of Flores in 1592 with a cargo of enormous value.

- Santa Catarina, seized by the Dutch East India Company off Singapore in 1603.

- Peter of Gdansk, a ship of the Hanseatic League in 1460-1470.

What was it used for?

The ratchet could be used as a merchant ship as well as a warship. Initially it was used for European trade from the Mediterranean to the Baltic.

However, with the new wealth of trade between Europe and Africa, and later with the Americas as transatlantic trade developed, it was soon used primarily to transport goods.

In its most advanced form, it was the Portuguese who used it most for commercial transport, moving their raw materials and products between Europe and Asia from the late 15th century.

In war, it was used to transport troops, including mounted armies.

Improvements over time

Many of the improvements to the ratchet were made in the late Middle Ages, particularly from the 14th century onwards. These changes included the addition of new masts, more sails, including lateen sails, changes that not only increased its strength and carrying capacity, but also its power as a large vessel that dominated the maritime trade routes.

They sailed from Iceland in the north, the Azores in the west and the coasts of Africa and even the Indian Ocean in the south. As time went on, significant improvements were made to the ship.

The most important of these was the introduction of a rudder with a rudder post to replace the spade rudders.

This rudder, in the nautical world, was the flat, vertical, movable piece that served as an extension of the rudder with which the course of the boat was determined.

It consisted of a plank, a piece of iron or a resistant polymer material, hinged to the stern or to the extension of the keel.

Its size and draught gave it very important and appreciated characteristics, such as the ability to transport large loads, being at that time the largest vessel for various loads, even complete troops.

Its strength was also underlined by the solidity of its hull, which made it reliable for transport, although its performance in stormy conditions left much to be desired.

However, the improvements made made it possible to improve the performance and efficiency of the ships and to make longer voyages.

Europe as a whole dominated shipbuilding at the time, thanks to these great vessels that enabled it to conquer new lands.

Later, the discovery of America and the consolidation of national states in Europe, such as England, Holland, France, Portugal and Spain, made it possible to raise significant funds to build larger fleets to explore the New World.

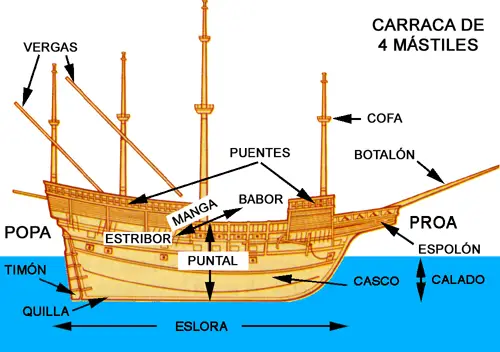

Characteristics of the carrack

The carrack was considered the great cargo ship of the 16th century, which saw the dawn of the Age of Discovery, during which new territories were discovered and cargo and troops were transported by sea to distant lands.

In fact, the famous Portuguese navigator and military explorer Ferdinand Magellan used ratchets on some of his expeditions.

The Ratchet was notable for its rounded, much larger, high-board hull, which allowed several bridges to be placed one above the other.

It had ample space to accommodate a large crew, provisions and the cargo necessary for the East India trade.

Her size and stability allowed her to carry guns.

She rose out of the water with a prominent forecastle, together with the usual sterncastle, giving her a characteristic ‘U’ shape.

The height of the sides made her virtually invulnerable to attack by small craft, which was often a problem in the East Indies.

The forecastle just above the stem, with the bowsprit protruding from the top, made it difficult to sail to windward, so it disappeared in later Gallants.

The square rig with lateen mizzen is typical of the period, but a second row of topsails was added to enable this heavy ship to be propelled.

The Ratchet was the first ship to have three masts on deck:

- The foremast, on which a sail was hoisted and which was called the foresail.

- The mainmast, which carried square sails called mainsail and topsail.

- The mizzen, which was the triangular lateen sail.

Later, a fourth mast was added, called the counter-mizzen, which was located at the stern with a lateen sail.

Over the years the sails became more complicated with the addition of new square sails to the first two masts.

The number of sails was increased to make sailing easier upwind and downwind, although they were counterproductive in a headwind.

The hull

This important frame, or the mostly submerged outer structure of the ratchet, provided buoyancy and also largely determined the ship’s manoeuvrability when sailing.

It was characterised by a ratio of about 3 between the length and breadth of the ship.

Both the high forecastle and the large sterncastle rested on the hull deck.

The forecastle, which supported the hull, was an integral part of this structure, unlike other ships where the forecastle was superimposed.

Also on deck were the combés, the space between the mainmast and the foremast or vertical mast at the bow, and the awning, or highest part, which served as the roof of the upper or sterncastle chamber. It extends from the mizzen or stern mast to the stern crown.

A cargo hatch was located in the combés.

The hull was reinforced with large straps and bulwarks, which were thick, wide wooden binders.

The sterncastle, also known as the stern quarterdeck, overlooked the entire main deck from the aft part of the ship and used to have more than two bridges embedded in the ship’s constitution where the guns were placed in battery after the doors were opened to increase the thrust.

This structure can also be seen in the aft quarterdeck, which, thanks to the strength of the hull, could be made up of two or more bridges called alcazarillos. War cannons could also be mounted.

Rigging

In nautical terms, rigging is the set of masts, sails, spars and rigging that allows the ship to move by taking advantage of the air currents that propel it.

The force of the wind is transmitted directly to the sails, which transmit it to the mast and rigging, depending on how the sails are arranged. The whole thing transmits the thrust to the hull of the boat.

Initially, ships were built with a single mast, then they evolved until, at the end of the 16th century, they had three masts and some even had four.

The masts had maststays, made up of each of the smaller masts, which were placed above the main masts on most round-sailed vessels.

These masts were used to support the topsails, bowsprits and jibs, and had cofas, or round wooden platforms, at the top of the main masts, where a bowman or lookout could be placed to watch for any danger that might be lurking on the ship.

On the ratchet, the most prominent mast was the mainmast. It was followed in height by the foremast and then the mizzen.

In the 15th century, the structure of the ratchet sail included the following parts

- Mainsail, sometimes called bowsprit, attached to the bowsprit mast.

- Quartersails, which were attached to the foremast of the foremast and the sail, the sail on the foremast.

- Quartersails for the mainmast and topsail.

- Mizzen lateen sail and mizzen or square sail for the mizzen topmast. Sometimes a lateen sail was used on the counter-mizzen, i.e. the mast facing more towards the stern.

Rigging

The rigging was an essential part of the ship, as it included all the masts to which all the sails needed for optimum navigation were attached.

The rigging was therefore part of the ship’s rigging and consisted of all the trees and spars of the ratchet, the word “tree” being used as a synonym for mast.

Over the years the rigging was replaced by an auxiliary engine, but in ancient times the rigging was an indispensable structure on sailing ships, being the only means of propulsion, so the rigging was even more important.

The rigging allows the sails to use the wind to propel the ship, the force of the wind being transmitted to the sails and the whole rigging transmitting the impulse to the hull.

The entire weight of the rigging is carried mainly by the masts, which are large vertical poles, and the spars, which are transverse poles that support the sails.

There is also the rigging, the ropes and cables.

There are many components of the rigging, among which we can mention

- The antenna, which is the metal tower on top of the ship’s hull.

- The rudder is the mast closest to the stern of the ship.

- Asta was the top of a masthead.

- Bita, any of the wooden or iron poles used to turn the anchor cables when the ship is at anchor.

- Boom, or long pole, pulled out from the outside of the ship when needed.

- Drop is the inclination or acute angle that a ship’s mast makes with the vertical.

- Candlestick is any of the vertical struts, usually of metal, placed at various points on a ship to secure ropes, canvas, battens or bars to form handrails.

- Crab or spar, having a semicircular opening at one end where it fits into the mast of the ship.

- A loop or cavity, usually square, into which a tree or similar piece of wood is fitted.

- Coz is the lower end of masts.

- Cross or centre of the mast with a symmetrical figure.

- Entena or curved and very long stick or pole to which the lateen sail is attached.

- The bunion is each of the spars that cross over the topsails and the sails attached to them.

- Different types of mastheads.

- Mecha, which is a kind of prismatic, square-shaped spike in which trees and other objects end at the bottom.

- Turnip or round wood that supports a cock.

- Pigeon, which is the middle part or cross of a pole.

- Percha, which is the whole trunk of the tree.

- Tamborete is the piece of wood used to attach a stick to another on top of it.

- Tiple or pole made from one piece.

- Tormentín is the small mast that was attached to the bowsprit.