Last Updated on September 27, 2023 by Hernan Gimenez

The mighty Indus River crosses three countries in Asia on its way to the sea. It has sustained many civilisations throughout the ages. We invite you to learn about its characteristics, its tributaries and its current situation. You will be surprised.

Indice De Contenido

Location and length of the Indus River

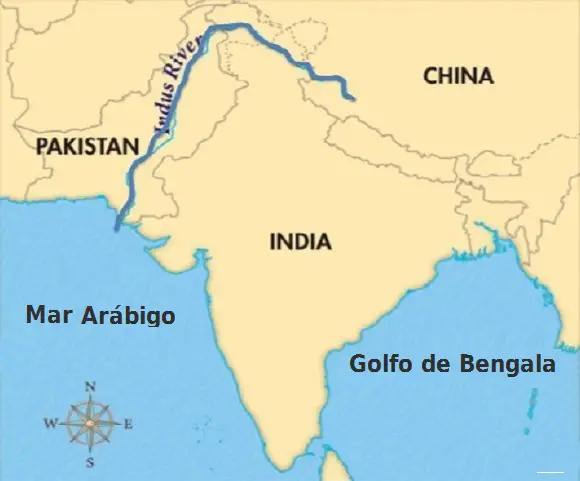

The Indus River is an Asian trans-boundary river in that it touches the borders of three countries, China, India and Pakistan, originating in China and flowing into the Arabian Sea in Pakistan after crossing the northern region of India.

It is also known as the trans-Himalayan river as it flows through this important mountain range in the Himalayas. We also recommend that you visit another interesting place such as the island of Bocas del Toro.

The Indus River has a total length of 3,180 km and drains a large basin of more than 1,165,000 km² in its Pakistani delta.

Its annual flow is estimated at about 243 km³, twice that of the Nile and three times that of the Tigris and Euphrates combined, making it one of the largest rivers in the world in terms of average annual flow.

The river’s flow is also determined by the seasons: it decreases significantly in winter, while it overflows its banks during the monsoon months of July to September.

The northern part of the Indus River valley and its tributaries form the Punjab region, a fertile alluvial plain with an extensive system of irrigation canals, much of it built under British rule.

Agriculture has flourished because of the heavy rainfall, which is distributed between the monsoon and winter seasons.

The lower reaches of the river end in its great delta in the southern province of Sindh in Pakistan. You may also be interested in the island of Fernando de Noronha.

The Indus has been historically important to many cultures in the region.

A major urban Bronze Age civilisation emerged in the third millennium BC, dating from about 4000 BC to 1500 BC.

During the second millennium BC, the Punjab region is referred to in the hymns of the Rigveda as Sapta Sindhu and in the religious texts of the Avesta as Sapta Hindu (both terms meaning ‘seven rivers’).

Among the earliest historical kingdoms to rise in the Indus Valley were Gandhāra and the Ror dynasty of Sauvīra.

The Indus gained prominence in the West in the early classical period when King Darius of Persia ordered his Greek subject Scylla of Caryanda to explore the river and spread its benefits around 515 BC.

The Indus provides key water resources for Pakistan’s economy, particularly for the breadbasket provinces of Punjab and Sindh, which account for most of the country’s agricultural production.

It supports the ecosystems of the temperate forests, plains and arid fields of these regions.

The Indus also supports many heavy industries and is the main source of drinking water in Pakistan.

The word Punjab means ‘land of five rivers’ because of the five major rivers that flow into the Indus in the region. These rivers are the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas and Sutlej.

One of the world’s earliest civilisations developed around these tributaries from the 3rd millennium BC.

Etymology and names

This river was known to the ancient Indians as Sindhu in Sanskrit and to the Persians as Hindu, and was regarded by both as ‘the river of the frontier’.

The difference between the two names is explained by the change in the sound of ancient Iran, which occurred between 850 and 600 BC, according to Asko Parpola, the renowned Finnish Indologist and Syndologist, an expert professor of Indology and South Asian Studies.

From the Achaemenid Persian Empire, the name passed to the Greeks as Indós (Ἰνδός) and was later adopted by the Romans as Indus.

Civilisations on the Indus River

The peoples living along the upper reaches of the Indus, such as the Tibetans, Ladakhi and Balti, show affinities with Central Asia rather than South Asia.

They speak Tibetan languages and practise Buddhism, although the Balti have adopted Islam. Pastoralism is important to the local economy.

In the main Himalayan ranges, the areas drained by the headwaters of the main tributaries of the Indus form a transitional zone where Tibetan cultural features blend with those of the Indian Pahari (hill) region.

Elsewhere in the Indus Valley, the inhabitants speak Indo-European languages and are Muslim, reflecting the repeated incursions of peoples who entered the Indian subcontinent from the west over several millennia.

The rugged mountains of western Kashmir are inhabited by Dardic-speaking groups (Kafirs, Kohistanis, Shinas and Kashmiri Gujjars) whose languages, like most of the languages of the region, are of Indo-European origin.

In the Hunza River valley, the long-lived Burusho speak a language (Burushaski) that is not known to be related to any other. These groups combine pastoralism with irrigated agriculture.

The Pashtun-speaking Pashtuns, who are closely related to the tribes of Afghanistan, predominate in north-western Pakistan.

The Yusufzai are the largest of the Pashtun tribes; others include the Afridi, Muhmand, Khattak and Wazir.

In the mountainous tribal areas of Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, the fiercely independent Pashtuns retain their traditional tribal structure and political organisation.

The well-watered northern Indus plains are inhabited by agricultural groups speaking Punjabi, Lahnda and related dialects, and are the largest population in the Indus Valley.

Language, ethnicity and tribal organisation play a minor role in group differentiation.

The main distinguishing feature among the peoples of the Punjab is caste, though without the religious and ritual connotations of the Hindu system. Muslim Jats and Rajputs are important Punjabi communities.

The lower Indus Valley is inhabited by agricultural peoples who speak Sindhi and related dialects.

Many of the region’s cultural traits appear to be of considerable antiquity, and the Sindhi people are proud of their regional distinctiveness.

Karachi, although in Sindh, is a predominantly Urdu city inhabited by Punjabis and Muhājirs, immigrants from India who came to Pakistan after the partition of the subcontinent in 1947.

Course and tributaries

On its journey from the mountains to the sea, the Indus River is fed by several tributaries that increase its flow, affecting the region through which it flows and thus its population, livelihoods and economy.

The Indus system is largely sustained by the snow and glaciers of the Himalayas, the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges of Tibet, and the Indian states and union territories of Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh and the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan.

Let’s take a look at the tributaries of the three countries affected by the Indus.

China

The ultimate source of the Indus is in western Tibet, in the Himalayas, where it rises at the confluence of the Sengge Zangbo and Gar Tsangpo rivers, which drain the Nganglong Kangri and Gangdise Shan (Gang Rinpoche, Mount Kailash) ranges.

The traditional source of the river, Sênggê Kanbab (also known as Sênggê Zangbo, Senge Khabab) or “Lion’s Mouth”, is a perennial spring not far from the sacred Mount Kailash, marked by a long, low line of Tibetan chortens.

There are several other tributaries nearby, possibly forming a longer stream than the Sênggê Kanbab, but unlike the latter, they all depend on snowmelt.

It rises from a mountain spring and is fed by glaciers and rivers in the Himalayan, Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges.

India

The Indus, as it flows through India, where it is often called the Sind River, flows through the northern part of the country, then northwest through the Ladakh regions of Jammu and Kashmir and Baltistan states to Gilgit in Pakistan, just south of the Karakoram range, which straddles the border between Pakistan, India and China.

It passes through the small towns of Nyoma and Upshi, from where the NH-21 road skirts the river, to the monastic area of Stakna, Mashro, Thikse and Shey, near Leh, the ancient capital of the Kingdom of Ladakh.

The Zanskar, which joins the Indus in Ladakh, has a greater volume of water than the Indus itself before it.

The Shyok, Shigar and Gilgit rivers contribute glacial water to the main river. This gradually bends south and descends into the Punjab plains at Kalabagh in Pakistan.

The Indus flows through huge gorges 4,500 to 5,200 metres deep near the Nanga Parbat massif. It flows swiftly through Hazara and is dammed at the Tarbela reservoir.

The Indus in this region is one of the few rivers in the world where the natural phenomenon of tidal surge occurs, creating waves as in the oceans.

Pakistan

In this country, the river crosses its entire territory and is of great importance for the development of its economic life.

The Kabul River joins the Attock River. The rest of its journey to the sea takes place in the plains of Punjab and Sindh, where the flow of the river becomes slow and very braided. The Panjnad joins it at Mithankot.

Beyond this confluence, the river was once called the Satnad (sat = ‘seven’, nadī = ‘river’), as it now carried the waters of the Kabul, the Indus and the five rivers of Punjab.

Passing through Jamshoro, it flows into a large delta south of Thatta in Pakistan’s Sindh province.

The Indus is one of the few tidal rivers in the world.

The climate of the basin varies from subtropical arid to semi-arid in the plains of Pakistan’s Punjab and Sindh regions to alpine in the mountainous areas near the river’s source.

There is also evidence of the river’s changing course since prehistoric times: after the earthquake of 1816, it was diverted westwards to flow into the Rann of Kutch and the adjacent Banni grasslands.

Today, water from the Indus flows into the Rann of Kutch during floods and overflows its banks.

The river’s delta is considered one of the most important ecological regions in the world.

Main tributaries

The major tributaries of the Indus along its downstream course are:

- Zanskar on the left bank, the first major tributary.

- Shyok, on the right bank

- Shigar, on the right bank, which flows into the city of Skardu

- Gilgit, on the right bank, with its tributaries Ghizar and Hunza

- Kabul, on the right bank, with its tributaries the Kunar and Swat

- Sohan or Soan on the left bank

- Tochi on the left bank

- Gumal on the right bank, with its affluents the Kundar and the Zhob

- Panijnad on the left bank, a short river of only 71 km, formed by the confluence of two long rivers:

- Chenab, with its tributaries the Jhelam and the Ravi.

- Sutlej, with its tributary the Beas.

Other smaller tributaries of the Indus include the Tanubal, Nagar, Astor, Balram, Dras, Ghizar and Kurram rivers.

Present situation of the Indus River

At present, a number of situations have arisen that have changed the behaviour of the Indus along its course. These modern issues include

The Indus Delta

Originally, the delta formed where the river empties into the Arabian Sea received almost all of the water from the Indus, which has an annual flow of about 180 billion cubic metres, accompanied by 400 million tonnes of silt.

Since the 1940s, dams, embankments and irrigation works have been built on the Indus, affecting its flow.

The Indus Basin Irrigation System is the “largest continuous irrigation system developed in the last 140 years” in the world.

In 2018, the average annual flow below the Kotri dam was 33 billion cubic metres and the annual silt discharge was estimated at 100 million tonnes.

As a result, the 2010 floods in Pakistan were seen as ‘good news’ for the ecosystem and the people of the river delta, providing much-needed freshwater.

Any other use of water from the river basin is not economically viable.

The vegetation and wildlife of the Indus Delta are threatened by reduced freshwater inflow, extensive deforestation, industrial pollution and global warming.

The dams have also isolated the Indus delta’s dolphin population from those further upstream.

Large-scale diversion of river water for irrigation has caused widespread problems. Sediment blockages due to poorly maintained canals have repeatedly affected agricultural production and vegetation.