Last Updated on September 27, 2023 by Hernan Gimenez

The Ganges, or “Ganga” in Indian languages, is the most important river source in India, both for its geographical location and for the role it has played in the religious traditions of the region, which consider it sacred as the embodiment of the goddess Ganga, the goddess of purification.

Indice De Contenido

Characteristics and location of the Ganges River

The river takes its name “Ganges” from the Sanskrit word “gángâ”, which means “going” or “moving fast”, alluding to its wide flow and long course through the Hindu region, fast and beautiful with its rituals, like the Paraná River in South America.

This river, together with the Brahmaputra, forms the largest delta in the world (see also the river delta known as the Ganges delta, in the Bay of Bengal, Indian Ocean, where it empties after its long and unique journey).

The Ganges has a length ranging from 2500 km to 3000 km, as well as a depth estimated at an average of 16 m and a maximum of 30 m. It is considered a great extension among the rivers of the planet and, in particular, a huge natural potential for India and the entire Asian continent.

The main origin or source of the Ganges begins in Uttarakhand, an Indian state located in the western Himalayas, specifically at the Bhaguirati source of Gomuhk, at the foot of the Gangotri glacier.

After a journey of about 210 km, it joins the Alakananda, which comes down from the Nanda Devi mountain, and from there it is called the Ganges.

It then flows eastwards, through the Haridwar region and into the northern plains of India, where it has given them the name of the Gangetic plains.

During its long course, the Ganges (see also: Mackenzie River) receives inflows from several other rivers that feed it, eventually draining a fertile basin of 907,000 km2 that is home to one of the highest population densities in the world, that of India.

The Ganges basin, which covers an area of 860,000 km, is now home to around 600 million people, almost half the population of the entire Asian country. A remarkable figure, which allows us to imagine the importance of the sacred river for all the daily and vital needs in the region’s daily life.

This enormous grouping, distributed along the length and breadth of the river, between towns and villages, coexists in the midst of cultural and religious manifestations that, beyond representing traditions and customs, have become inescapable rituals that transcend the borders of the planet. The Volga is a millenary river, like other Asian and European waters, and a colourful destination,

In addition to this imposing population, there is an exodus of tourists and visitors who come to share the benefits of the mighty river for a variety of reasons.

On the other hand, this important and extensive river of Asia flows into the Ganges delta, whose environment is a wonderful recipient of a rich variety of flora and fauna of the region.

The Sundarbans National Park, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in the 1990s, is located in this area, thanks to the ecological richness of these forests, a natural paradise and the original habitat of the famous Bengal tiger, among other species.

Tributaries of the Ganges

Major tributaries of the Ganges include The Yamuna River, 1300 km, also considered holy, at Allahabad; the Ghaghrâ River, 1080 km, at Châpra; the Gandak River, 700 km, at Hajipur; the Râmgangâ River, 640 km, near Allahabad; the Sone River, 784 km, at Patna; the Dâmodarâ River, 541 km, south of Calcutta; the Koshî River, 700 km, near Bhagalpur; and the Gumtî or Gomatî River, 675 km, near Benares.

Countries crossed by the Ganges River

This major Asian river flows through parts of Bangladesh, Nepal and China, as well as a large part of India.

Some 600 million people benefit from its extensive waters, not to mention the additional influence it exerts on the activities of millions who visit for religious pilgrimage and other purposes.

Since time immemorial, the Ganges in India has been a means of interaction between indigenous and foreign communities, exchanging all kinds of activities, from religious and family, to commercial, industrial, domestic, tourist, scientific, or simply curiosity and entertainment, making it famous throughout the world for its characteristics and benefits, which in turn attract more and more people to visit it.

The river is Asian, but its course is witness to the exchange of various international cultures and customs, especially those coming from countries close to India, such as Nepal, Bangladesh, China, Pakistan and many others.

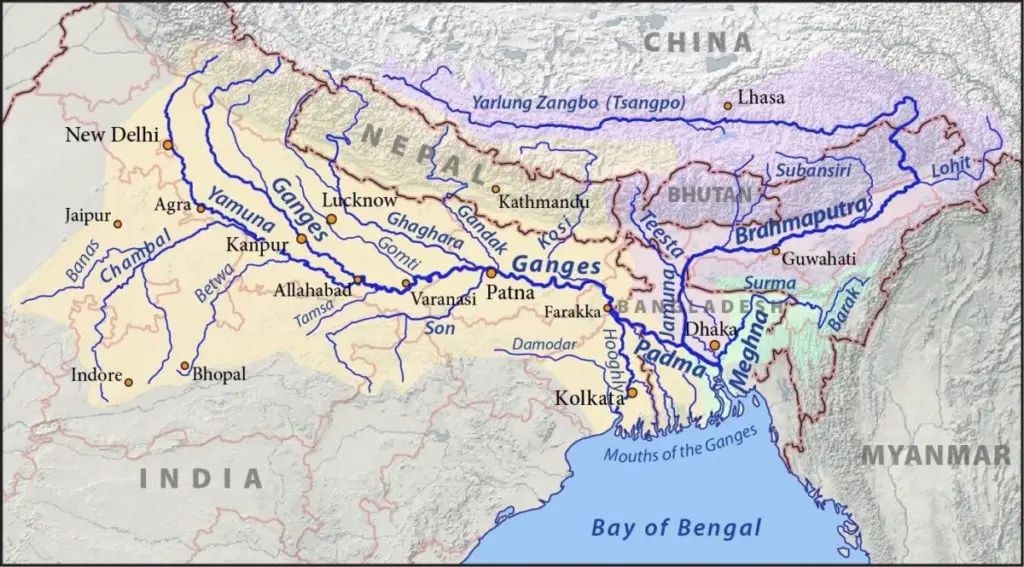

Map of the Ganges

The location and course of the Ganges River in India can be seen on the map below, along with its source and mouth.

Importance of the Ganges

The Ganges, along with other rivers in Asia such as the Yangtze, is of great historical, geographical, commercial, economic and cultural importance. Not only for its own people, but also for the rest of the world, since its fame as a sacred river for Hinduism, among other special characteristics, arouses many concerns that invite people to travel to its waters.

People from all over the world flock to the major cities along the Ganges for a variety of purposes. Be it for tourism, business, family reunions, religious pilgrimage, cultural exchange, business, study, in short, whatever the reason for their passage, they bring novelties and economic movements that benefit the local inhabitants themselves.

Since ancient times, many important cities have been located near the river. Today, some of the most important cities are: Varanasi, Calcutta, Patliputra, Kannauj, Kara, Allahabad and Murshidabad.

With more than 600 million people living in the regions around the Ganges, the area generates more than 40 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). This represents a significant productivity in India’s economic system and an undoubted incentive to meet the needs of its infrastructure and maintenance, and to ensure the sustainability of its waters over time.

In addition to the local and foreign people who share its waters, many species that converge on its banks and depths are affected or benefited, depending on the level of hygiene, health and optimisation that the Ganges presents.

The fertile soils of the delta are used to grow rice, wheat, potatoes, lentils, sugar cane and some oil seeds. But the agricultural areas, which use 90 per cent of the river’s water for irrigation, are also home to India’s largest number of poor people, some 200 million.

Numerous factories and industries have sprung up along its banks to exploit its resources and have developed rapidly in recent decades, suggesting latent potential for further expansion in the future.

The water itself is used for irrigation, domestic activities such as washing, cooking, personal hygiene and others, and of course the traditional fishing of the region. The Ganges delta (see also Nile delta), known as the Sundarbans, is a privileged region characterised by dense mangrove forests, one of the main habitats of the Bengal tiger.

This area, declared a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) in 1997, is home to the Sundarbans National Park, with a protected area of 1,395 km2.

Tourism is an important source of income and movement for India. The Ganges River is part of the attraction of visiting this region.

Why is the river Ganges sacred?

The followers of the Hindu religion believe that the river Ganges is the goddess Ganga, who reigns over purification, and that by bathing in its waters, consuming it or scattering the ashes of their dead, they will purify their souls to reach Nirvana or Paradise directly, without having to repeat several reincarnations.

There is a legend that in ancient times the Ganges River flowed through the sky while the lands of India were dying of thirst, until King Bhaguiratha washed the ashes of his ancestors and caused the waters to fall.

As this fall would have been very violent and would have caused destruction throughout the land, Shiva first caused it to pour over his head, allowing his hair to cushion the passage of the water for a thousand years, until the sacred river in the Himalayas was created, with a softer and more moderate flow, reducing the risk to the settlers.

Rituals on the Ganges

In the same way, they believe that the body should be cremated on the banks of the Ganges and the ashes scattered over it in order to be purified once and for all and gain direct access to the realm of Nirvana, avoiding the need for further reincarnations. According to these beliefs, any body cremated in the Ganges or Ganga is freed from moksha, or karma.

It is estimated that an average of 100,000 Hindus flock to the holy city of Haridwar every spring to celebrate the birth of Mother Ganges through their rituals and customs.

They place small boats made of leaves on the waters of the river. These are filled with flower petals, especially marigolds, dipped in ghee or clarified oil, which is used to light them before they are launched.

They perform dances, chants and cries that complement other rituals, along with the process of cremating bodies and offering them to the gods.

Everything is carried out by castes who divide up their tasks. For example, in the city of Varanasi, the holiest city in the Hindu religion and known as the City of Light and Death, the Doms are in charge of cremations and families must pay them and meet the necessary requirements, including firewood and incense for the ceremony, the cost of which is beyond the reach of most families in India.

Gangetic river dolphin

One of India’s most famous and recognisable species, along with the Bengal tiger, is the Gangetic river dolphin, named after its habitat in the river of the same name.

One of its special characteristics is its ability to adapt to the different changes in the environment, depending on the season and whether it is alone or in a group.

Found only in the freshwater rivers of Bangladesh, India and Nepal, it is currently considered endangered because it is a different species from the Orinoco dolphin.

It is also different because, unlike other dolphins that move quickly to catch their food, the Gangetic dolphin moves slowly. It therefore feeds differently and tends to stay deeper in the river. It feeds on fish, turtles and birds that live around the river.

Physiognomically, the Gangetic dolphin has large fins, a longer snout than other species and its body is also larger and heavier. It is these dimensions that distinguish it from other dolphin species. A small one can be about 5 feet long and weigh about 200 pounds.

On the other hand, their reproduction is very similar to that of other dolphins, giving birth to a single calf at a time, which is born after a waiting period of 10 to 12 months. Females reach reproductive maturity at 6 to 10 years of age, and calves remain with the mother for the first year and are nursed.

Other species found in the Ganges include the Ganges shark (glyphis gangeticus), the gavial (gavialis gangeticus), about 140 species of fish, 90 species of amphibian and 5 species of freshwater cetacean.

Dead in the Ganges

Can you imagine the Ganges River as a morgue? It would seem so. The cultural and religious rituals that promote the cremation of corpses in order to purify oneself and achieve direct access to Nirvana, avoiding reincarnation many times over, are undoubtedly important and transcendental for the followers of Hinduism, but they are only part of the customs that take place daily in the waters of India’s most important river.

This practice, which is usually carried out in different categories according to caste and economic means among families in this Asian region, often gets out of control and ends up in incomplete or careless cremations, with cheap materials and high levels of pollution.

As a result, the remains of corpses are often found floating in the waters of the Ganges, developing processes of decomposition that are shared by those who come to bathe, wash and even consume the precious liquid of the sacred river.

These bodies are “deposited” in these waters with full consciousness and will, for reasons that obey religious beliefs and rituals.

Along with them, other human remains, which for various reasons are not cremated but thrown whole into the river, as well as the bodies of animals, end up in the same watery graveyard. A common and particularly striking case is that of cows, which are not touched before or after death because they are considered sacred.

So much devotion to the river around death makes it an image that reflects it. In addition, the serious consequences of the process of transformation and decomposition of so much organic matter in its waters make the Ganges an imminent and latent risk of death.

Contradictorily, the gentle, cleansing and healing waters of the Ganges are becoming a deadly threat to its usual visitors, who in turn return to it time and again in search of life, harmony, health and peace.

How to deal with this paradox and maintain a balance for the benefit of the regular visitors to this vast and beautiful river is not an easy question to answer. But the ecological restoration of the ecosystem and the entire environment surrounding the Ganges requires the will of the entire planet to find a way forward to prevent the growth of further threats.

Pollution of the Ganges

Pollution in the Ganges is exorbitant. It has reached such high levels that hundreds of towns and villages in the surrounding area, as well as the flora and fauna that live there, are at serious risk of serious diseases and epidemics.

The rapid industrialisation of the country in the 1990s, coupled with unstoppable population growth, is one of the causes of India’s environmental degradation. The way certain religious and cultural aspects are dealt with does not help, and unlike other rivers such as the Thames, it has deteriorated very rapidly.

Poor and improvised drainage systems are a major cause of this pollution. All urban drains end up in the Ganges to discharge their waste. About 300 million litres of sewage flow into the river.

In addition to the wastewater from homes, farms, businesses and the many buildings that support life in India’s various cities and towns, there is also the growth and increase in the number of factories in general, which are growing rapidly in a world of highly developed industrial inputs and which discharge toxic substances into the water.

These industries indiscriminately dump their waste into the Ganges, including various types of materials and heavy metals such as chromium or cadmium, contributing to its high level of pollution.

The continuity and frequency of rituals and cremations in the Ganges are also a major source of pollution.

All followers of the Hindu religion bathe in the waters of the Ganges at least once a year. This means that people can always be seen in its waters.

The banks of the Ganges bear witness to the countless acts of devotion and faith that each and every follower of the Hindu religion performs on a daily basis. Paradoxically, these daily acts of seeking purification of the soul contribute to the increase of impurities in the water to life-threatening levels.

If we consider that around 32,000 bodies are cremated in the Ganges every year in poorly controlled conditions, we can estimate that a large number of human remains drift along the river and decompose in its waters, causing serious levels of pollution.

In addition, not all bodies are cremated; for example, pregnant women, children and people considered ‘pure’, without sin, are thrown directly into the river. Cows, considered sacred by the Hindu population, also suffer this fate. And many corpses from various circumstances are also thrown into the Ganges.

Cremation is a high economic cost that many families cannot afford, so they often use various materials that are even more inappropriate and make the situation worse. The large amount of rubbish produced by a population of India’s enormous density, which is dumped unchecked in every part of the cities and in the river, also contributes to the pollution of its waters.

The Ganges contains 60,000 faecal bacteria per 100 millilitres of water, which is 120 times higher than the limit considered safe for bathing. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has declared the waters of the Ganges unfit for human consumption.

The species of flora and fauna that inhabit the Ganges ecosystem are also caught up in the pollution and affected in their development. Many are considered endangered due to this serious problem.

Misinformation and neglect on the part of local and regional authorities are adding to this breeding ground for very high risks of disease. Despite mounting warnings, the existence of specialist scientific reports and studies, and various programmes to address the situation, little progress has been made in cleaning up the river.

The governments involved are ignoring the problem, using cultural and social arguments that probably mask different interests and prevent concrete action from being effective.

Over time, as India’s population grows and the influx of people to the Ganges increases, so do the threats to biodiversity and environmental sustainability. Despite efforts to clean up the river, they have not been enough. Cases such as this, in rivers of great importance to the region, are worrying, as they also occur on other continents, such as the Caroní River in South America.

Unless much closer and more effective action is taken to improve the appropriate infrastructure around the river, the consequences could be unimaginable and catastrophic. New approaches to environmental management and technical expertise are needed to find solutions and reduce pollution.

Awareness campaigns are urgently needed to prevent the proliferation of both organic and inorganic waste, including from foreign visitors, as well as garbage, toxic materials, polluting metals, dead bodies and other environmentally harmful substances and devices that flow into the Ganges.

But there is also a need for such conscientiousness on the part of the authorities concerned to develop direct treatment plans for each pollution problem.

Diseases of the Ganges

Infectious, respiratory and skin diseases are increasing at an alarming rate among the people of India who bathe daily in the waters of the Ganges.

The same happens with parasitosis, conjunctivitis and many other diseases caused by contact with bacteria that multiply in the humidity and pollution. There are very serious and fatal cases that are not treated in a timely and appropriate manner by the victims themselves or by their relatives because they are “clouded” by religious beliefs and traditions.

The most common serious illnesses are those caused by E. coli bacteria, which cause severe diarrhoea, dehydration and all the processes of digestive complications that can lead to death by septicaemia.

Major world organisations, NGOs, associations, foundations and institutions of various kinds are showing interest and projects to clean the waters of India’s most famous river and to help its people and government authorities develop policies and plans for its future maintenance. The Ganges and its dedicated people deserve it.