Last Updated on August 25, 2023 by Hernan Gimenez

The Guadalquivir River is a large river source in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and occupies the fifth place in this region, according to its extension along the territory that crosses several provinces of Spain.

Indice De Contenido

Origin of the name Guadalquivir

The name Guadalquivir comes from the Arabic word al-wadi al-Kabir الواديالكبير, which means ‘great river’. This was not the only name given to this mighty river in northern Spain. The first name it adopted was Baetis or Baitis, the origin of which is attributed to the pre-Roman period, although it is not fully attested.

This name, Baetis, could be of Celtic, Iberian or Ligurian origin. In ancient times, the root baet or baes was very present in Spain, France and Belgium, and was used to form toponyms, the names of various tribes and a variety of gods.

There are also hypotheses, based on various studies, that the Phoenicians called the river Betsi, which is a Canaanite word. As if that were not enough, around the 7th century BC, some Greek navigators named the present-day Guadalquivir River Tharsis, referring to the kingdom of Tartessos. Although it is also known that the Tartessians themselves continued to call it Baetis.

Later, even after the Roman conquest, the name was kept as Baetis or Betis. However, there are references to the river with other names, such as Stephen of Byzantium, who called it Perkes or Perci, or Titus Livy, who called it Certis.

With the arrival of the Arabs, from the time of Rasis and the establishment of the capital in Córdoba, the river began to be called NahrQurtuba (River of Córdoba), although they maintained a certain relative respect for local names.

But as the Caliphate of Cordoba declined, the Arabic word for river, nahr, was replaced by wad. This word comes from wed, the name given to the great wadis of the Sahara and the Maghreb.

This is how the Rio Grande came to be called Wad al-Kabir, which later became Al-Kabir and then Kabir to Kibir, a product of the Hispano-Arabic phenomenon known as “imála”. As early as the 13th century, during the visit of Fernando III to Seville, the river was known as Guadalquebir or Guadalquibir, from which it evolved a little until it became the Guadalquivir we know today.

Source of the Guadalquivir

Where does the Guadalquivir originate? This river rises at 1,400 metres above sea level in Cañada de las Fuentes, in the municipality of Quesada, in the Sierra de Cazorla, in the province of Jaén (see also: Mississippi).

Its waters flow 657 kilometres from the Sierra de Cazorla to Sanlúcar de Barrameda, in the province of Cadiz. As it flows through the autonomous community of Andalusia, it crosses the beautiful and important lands of Jaén, Córdoba and Seville, providing water for different uses such as domestic, agricultural, industrial, commercial and other activities in the area, reminiscent of the beautiful landscapes of the Iguazú River in other latitudes.

The hydrographical basin of this great European river includes parts of the eight provinces of Andalusia, as well as parts of the regions of Murcia, Albacete, Ciudad Real and Badajoz.

Specifically, its route includes towns such as Mengíbar, Villanueva de la Reina, Andújar and Marmolejo, in the province of Jaén; Villa del Río, Montoro, El Carpio, Córdoba and Palma del Río, in the province of Córdoba.

Also Peñaflor, Lora del Río, Alcolea del Río, Villanueva del Río, Villaverde del Río, Brenes, Alcalá del Río, La Rinconada, La Algaba, Camas, Sevilla, San Juan de Aznalfarache, Gelves, Coria del Río and La Puebla del Río, in the province of Sevilla; and finally, Sanlúcar de Barrameda and Trebujena, in the province of Cádiz.

Mouth of the Guadalquivir

At the end of its long course, the Guadalquivir flows into the Atlantic Ocean, reaching Almonte in the province of Huelva and Sanlúcar de Barrameda in the province of Cádiz.

There it opens up and forms a typical wide estuary, around 500 metres wide where it opens up and around 4 kilometres wide where it enters the open sea, which is considered to be of great environmental value due to the rich biodiversity it shelters.

Between Seville and the estuary is a vast wetland area known as the Guadalquivir Marshes. Its biodiversity is reminiscent of that of the Orinoco.

Tributaries of the Guadalquivir

The tributaries of the Guadalquivir can be divided into two groups according to their location in relation to the Guadalquivir. They all have in common that those on the left bank of the Guadalquivir are longer than those on the right, and they generally flow in a southeast-northwest direction.

Among the rivers that flow along the banks of the left bank of the Guadalquivir are the following:

- Guadiana Menor river, with 182 km and historically and technically considered the true source of the Guadalquivir.

- River Guadalbullón, 74 km long and passing through Jaén.

- River Guadajoz, 114 km long.

- River Genil, 337 km long and estimated as the main tributary of the Guadalquivir River, which brings it approximately 33 m³/s, collecting the waters of the Sierra Nevada and passing through Granada (together with the Darro River), through Loja, Puente Genil and Ecija.

- River Corbones with 177 km.

- River Guadaíra, 89 km long, passing through Alcalá de Guadaíra and Seville.

- River Tamarguillo, which flows through Seville (see other rivers in Spain such as the Segura river).

On the other side of the Guadalquivir, to the right, the tributaries, also known as the Marianic, form a poorly articulated network. They seem to be independent courses with a certain equidistance, but heading for the same destination. They start their journey from the peninsular peaks of the Iberian massif and flow down the flanks of the Sierra Morena. Among these tributaries are

On the other side of the Guadalquivir, to the right, the tributaries, also called Marianic, form a poorly articulated network. They seem to be independent courses, with a certain equidistance, but heading towards the same destination. They start their journey from the peninsular peaks of the Iberian massif and flow down the flanks of the Sierra Morena. Among these overflowing rivers we have:

- Guadalimar river, with 167 km.

- Jándula river, with 90 km.

- River Yeguas, with 76 km.

- River Guadalmellato, 111 km.

- River Guadiato, with 123 km.

- River Bembézar, 111 km.

- River Viar, 117 km.

- River Rivera de Huelva, 61 km.

- River Guadiamar, 60 km

Guadalquivir reservoirs

The Guadalquivir basin (see also Nile basin) has a storage capacity of 8,782 m³ and its main reservoirs are: the Tranco de Beas reservoir, with a capacity of 498 m³, in the river itself and in its tributaries:

- Iznájar reservoir, on the river Genil, with 981 hm³.

- Negratín reservoir, on the river Guadiana Menor, with 567 hm³.

- Giribaile reservoir, on the river Guadalimar, with 475 hm³.

- Bembézar reservoir, on the river Bembézar, with 342 hm³.

- Jándula reservoir, on the river Jándula, with 322 hm³.

Map of the Guadalquivir river

As for the location of the Guadalquivir River, where it rises and where it flows through, the map of the Guadalquivir River is shown below for better information.

This is the only river in Spain with significant river traffic, although it is currently only navigable from the sea to Seville. In tourism, boat trips are used to discover its incredible waters, as much for adults as the Guadalquivir River is for children.

Commercial navigation on the Guadalquivir River has a channel called the Eurovía Guadalquivir, which is included in the European network of navigable waterways as part of the TENT network of transport of European importance, under the auspices of the European Union.

Throughout the history of European rivers, the Guadalquivir has played a role in the transport of goods by sea in the section of its estuary that bears its name, and today it functions in a way that is appropriate to its configuration and use, in accordance with the requirements of modern shipping.

To use the route of this imposing river, the port facilities of the city of Seville must be reached through the lock, the only one of its kind in Spain, which comes from the Atlantic Ocean at Sanlúcar de Barrameda.

The lock connects the Eurovía Guadalquivir with the great port of Seville, with the essential function of serving as a ship lift from the Eurovía Guadalquivir to the commercial port of Seville and vice versa, as well as sharing functions of protecting the city, mainly by closing the defensive wall against possible floods and levelling the waters.

Loading and unloading operations are carried out there for the international export of goods or their transfer to other areas of Spanish territory, as well as commercial transactions for the distribution of imported goods that are then transported by land.

The Guadalquivir River Walk, on the other hand, begins at the emblematic site of Seville’s famous Torre del Oro (Tower of Gold) and crosses the entire marshland and part of the Coto de Doñana to the Atlantic Ocean, passing through the port area, old bridges and some of the newer ones, such as the Puente de las Delicias, a drawbridge that allows ships to enter the marina, or the Puente del Centenario, built for the 1992 World Expo in Seville.

It passes through the Exclusa, some villages such as Gelves, Coría del Río and Puebla del Río, the marshlands of Seville, rice fields and the Coto de Doñana National Park, before arriving at the spectacular mouth of the great river and Sanlúcar. A place as magnificent as the Rio de la Plata.

Guadalquivir Since Forever

It is known that the Guadalquivir has been navigable since ancient times, with the first rudimentary attempts being made with wooden canoes. In Roman times, ships were able to navigate its currents as far as Cordoba and, at certain times, as far as Andújar. Its waters have seen the passage of civilisations that have played a decisive role in Spanish history. The Phoenicians, Tartessians, Iberians, Romans and Arabs all left their mark on the course of this great river.

During the Roman period, its currents allowed ships to reach Cordoba and, at times, even Andújar. Products from the East were traded and distributed throughout Hispania through a port that existed in the area.

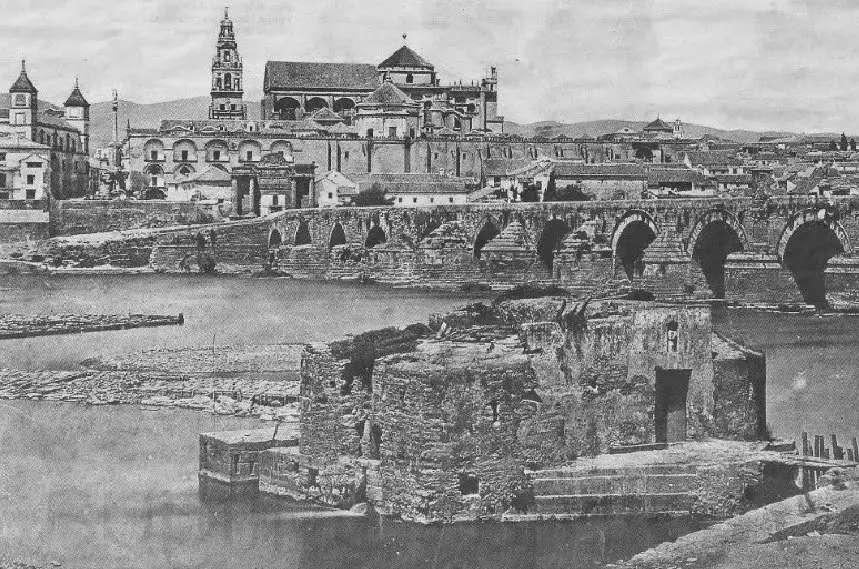

After the construction of the Roman bridge in the 1st century AD, the port was consolidated very close to the entrance to the city, in the area of what is now the water wheel of La Albolafia. From this place, shallow-draft boats transported products to the large merchant ships anchored in the sea to take them to Rome.

[For centuries, the river was the fastest and most efficient means of trade in the Mediterranean, facilitating communication and transport in the face of the complications of land transport.The Guadalquivir River had its highest navigable point in Cordoba since the early Middle Ages. Later, the importance of the river port of Cordoba diminished until the time when the port of Seville was consolidated, due to the changes brought about by the discovery of America.

There have been several attempts to improve navigation on the Guadalquivir since ancient times, such as the proposal by Fernán Pérez de Oliva, who insisted for a long time in the 16th century that navigation to Cordoba should be possible, but his attempts were unsuccessful.

We also know the project of the Mengemor company, presented in 1904, which led to the construction of several dams on the river, such as those of Posadas and Palma del Río, as it introduced the idea of placing 11 dams in a staggered manner so that the reservoirs would guarantee a minimum draught of 2 metres, where navigation could be achieved.

The Romans continued to navigate the Guadalquivir and were able to expand trade with Italy. The Goths did not abandon it and it continued at least until the reign of Henry III, who sailed from Cordoba to Seville in 1402.

In 1360, the owners of some mills closed the passage to ships, whose owners complained to the kingdom, which ordered the mayor of Cordoba to determine the space for the mouths. The resulting rule was the width equivalent to the Arch of Blessing of the Cathedral (28 feet) and determined that the depth should be 6 feet.

Navigation was then resumed, but later stopped again for fear of robbery by the Moors of Granada. Much later, in 1528, the great enterprise of navigating the Guadalquivir to Cordoba was resumed, in view of the many enormous benefits it would bring to the prosperity of Andalusia. However, the matter was always postponed due to the more pressing priorities of the time.

In the 16th century, attempts were resumed and experts were sent to Córdoba, who overcame great obstacles and built boats from the province of Jaén and the Sierra de Segura, without much success. The French also made an effort and reopened the inland trade on the waters of the Guadalquivir, respecting the weirs and without adequate works for the passage. They built very shallow boats with a maximum load of 18 inches, and on several occasions took wheat and other goods to Seville.

When the French left, navigation ceased again, and after several other projects, plans, budgets, reactivations and collapses, new regulations and modifications continued to be enacted to optimise the conditions of the river, until we reach the present day, where the risks and inconveniences persist, but with, of course, a better flow along the route.

The course of the Guadalquivir

The Guadalquivir flows from east to west, turning south in the province of Seville. Almost all of its 657 kilometres run through the plain known as the Guadalquivir depression, which widens until it reaches the estuary, reaching a width of 10 kilometres in Úbeda, 60 kilometres in Córdoba and 330 kilometres in its final stretch.

The course of the river Guadalquivir follows several slopes, which can be divided into three main courses: upper, middle and lower.

The upper course of the Guadalquivir

The upper course of the Guadalquivir begins in the Sierra de Cazorla, at about 1,350 metres above sea level. It flows through the Cerrada de los Tejos, El Raso del Tejar, La Espinarea, Cerrada de los Cierzos and Puente de las Herrerías. At Vadillo (Cazorla) it slows down a little at the small reservoir of the Cerrada del Utrero, around 980 metres above sea level.

It then descends through the Cerrada del Utrero, passing through the Arroyo Frío, in La Iruela; it crosses the Puente del Hacha and La Herradura bridges and then skirts the Cabeza Rubia hill. As it descends, it receives water from the rivers Borosa and Aguamulas, on the right bank.

It rises again at the level of the Tranco reservoir, 650 metres above sea level, to turn west and cross the Sierra de Las Villas, next to the Charco del Aceite, receiving on the left the Arroyo de María and the Arroyo del Chillar, to finally leave the Sierra de Cazorla, Segura and Las Villas Natural Park.

It reaches the olive grove plain 15 kilometres from Úbeda, where it receives water from the Rivers Guadiana Menor and Jandulilla. It continues and, after passing through the village of Puente del Obispo, in Baeza, it receives the River Torres on the left and, further downstream, the River Guadalimar on the right.

The upper course, from its source to Mengíbar14, is about 212 kilometres long and has an average gradient of 6.7 per thousandth.

Middle course

It begins at the edge of the Sierra de Cazorla, Segura and Las Villas Natural Park and heads southwest, crossing the municipalities of Agrupación de Mogón (Villacarrillo) and Mogón (Villacarrillo), where it joins the River Aguascebas on its left bank and, a little further down, the River Cañamares. It reaches the village of El Molar (Cazorla) and then the Puente de la Cerrada reservoir, about 350 metres above sea level.

Fed by the River Guadiana Menor, it passes through the reservoir of Doña Aldonza, where it joins the River Jandulilla, and then it reaches the reservoir of Pedro Marín and, after passing through the Puente del Obispo, the River Torres and the River Guadalimar.

Heading northwest, it reaches Mengíbar, where it joins the River Guadalbullón on the left and the River Rumblar on the right. To the south, the Sierra Morena passes through Villanueva de la Reina and Andújar, shares the waters of the river Jándula, passes through Marmolejo and joins the river Yeguas on the provincial border with Córdoba.

The middle section runs from Mengíbar to Peñaflor and is 247.8 kilometres long, with an average gradient of 0.73 per thousandth.

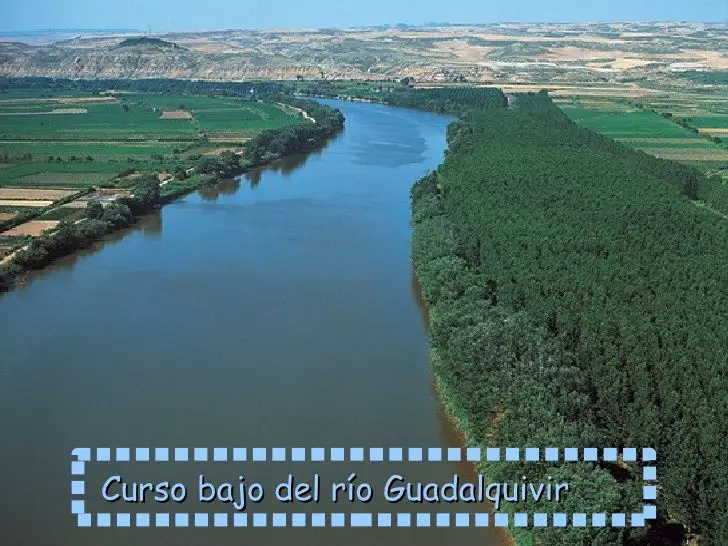

Lower course

The Guadalquivir reaches Villa del Río and Montoro, it joins the rivers Arenoso and Guadalmilla, it crosses Córdoba and joins the rivers Guadajoz and Guadiato, in Almodóvar del Río. It passes through Posadas and joins the river Bembezar and then the rivers Retortillo and Genil in Palma del Río. With long stretches similar to those of the Uruguay.

It enters Seville, passing through Peñaflor, Lora del Río, Alcolea del Río, Tocina and Cantillana, where it joins the river Viar. It continues to Villaverde del Río, Brenes and La Algaba, where it joins the Ribera de Huelva. It also receives the river Guadaíra, passing through the villages of Aljarafe.

After leaving Coria del Río and La Puebla del Río, the river divides and forms semi-mountainous areas called the Marismas del Guadalquivir. To the west is the Doñana National Park, and between Cádiz and Huelva it flows into the Atlantic Ocean at Sanlúcar de Barrameda.

Environmental value of the Guadalquivir

The area of the Guadalquivir River, which includes the provinces of Seville and Cadiz, has a great aquatic biodiversity, considered to be the greatest in Andalusia and one of the most important in Europe.

The brackish waters of this stretch of the Guadalquivir, where the currents from the sea meet those of the river, allow the great biodiversity that characterises it to flourish.

However, it is also particularly important for its role in sheltering the larval series of species that require strategies such as spending the first stage of their life in an area where the presence of any marine or freshwater predator can be avoided, thanks to the peculiar condition of belonging neither to the river nor to the sea. Its beauty is imposing and refreshing, as on the banks of the River Solimoes.

On the other hand, all the nutrients in the river basin are concentrated in this section of the Guadalquivir, which means that there is plenty of food for the many fish and invertebrates whose larvae or juveniles use the estuary to “grow”.

Some of the commercial species that develop in the Guadalquivir using this type of strategy and then migrate to the sea when they reach maturity are anchovies, sorrels, soles, dab, sea bass and shrimps, among many others, which in turn provide food for the inhabitants of the fishing grounds in the Gulf of Cadiz.

Ecosystem of the Guadalquivir

We can find different species of flora such as the laricio pine, white poplar, southern holm oak and in the Betic Mountains we can find strawberry trees. In Andalusia, the typical tree is the cork oak, but its large forests are found in the middle riverbed, where it is normal to find cherry trees, ash trees, chestnut trees, hackberry trees, jacaranda trees, cinnamon trees and pomegranate trees.

The fauna is also very varied, with mammals, birds and fish. We can find mammals such as the lynx, in the high and mountainous areas we can find the mountain goat, wolves, mouflons, weasels, genets and we can also find otters in all its cause.

As for the birds that can be found along the Guadalquivir, we can find the imperial eagle, flamingos, hollyhocks, stilts, brown teal, griffon vultures and crayfish.

Among the fish that inhabit the river are the calandino, eels, eel, bleak, carp, carp, carpine, catfish, rainbow trout, perch, catfish, pike, chanchito and many other species that decorate the fauna of this majestic river.

Guadalquivir in Bolivia

In South America, in Bolivia, there is a river called the Nuevo Guadalquivir, or Guadalquivir a secas, due to its resemblance to the original river in Andalusia, Spain.

The Nuevo Guadalquivir is located in southern Bolivia and flows through the city of Tarija, capital of the department of the same name.

The Nuevo Guadalquivir is located in southern Bolivia and flows through the city of Tarija, capital of the department of the same name. It is considered to be only the middle section of a river formed by the contribution of other rivers, all on Bolivian territory, such as the Chamata, the Vermillo and the Trancas, among others, which originate about 50 km northwest of the city of Tarija, on the eastern slopes of the Sama mountain range, at an altitude of 3400 metres.

The Nuevo Guadalquivir has been suffering from serious pollution problems for about a decade, for a number of reasons, the most important of which is the accumulation of rubbish and waste of all kinds thrown into the river itself or into its tributaries.

The river has its source in the municipality of Tomatas Grande and retains its name until it joins the Camacho River, 36 kilometres southeast of Tarija, in an enclave called La Angostura, where it begins to be called the Tarija River.

The Nuevo Guadalquivir is fed by the Carachi, Mayu, Sella and Yesera-Santa Ana rivers on its left bank and by the Calama, Erquis, Santa Victoria, Tolomosa and Camacho rivers on its right bank.

It belongs to the hydrological group called the Tarija-Bermejo sub-basin, which includes the transformations of the Guadalquivir itself, which changes its characteristics and name. Thus, after passing through La Angostura, the Tarija River follows a very narrow and varied course until it joins the Itaú River. From there it changes direction and is renamed the Grande de Tarija River in the border area between Bolivia and Argentina.

The Río Grande de Tarija then joins the Bermejo River, which flows into the Río de la Plata.